Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde puts the rock back into the Byrds’ particular brand of country rock. The record is patchy and poorly recorded, with Bob Johnston’s thin, hollowed-out production value perhaps standing as an instance of incipient corporate rock, where craft becomes subordinate to efficient movement down the creative assembly line. It’s too bad because a slog through the record’s murkiness reveals, here and there, the amazing things that can happen with the interwoven guitar playing of Roger McGuinn and Clarence White. It seems to me that by now the Byrds were pretty much a live band. Their studio output from here on out doesn’t match the intensity of what they’re able to do on stage and in the moment. This is great if you like stretched-out live music. You’ll love every noodling second of the 15-minute all-instrumental rendition of Eight Miles High. But those of us who crave the precision, the artistry, and (hopefully) the attention to detail that studio recording affords will be a little leery. And yet, I come back to McGuinn and White. Their chemistry is electrifying. They really seem to relish being on stage together, an old folkie and a blue grass picker, completely simpatico in making rock that sounds huge and isn’t at all diminished by its country overtones. But having said all this, tonight’s song feels a bit nostalgic. You’ll never mistake it for pop, but the song has a folk-ish melodic structure that almost gets lost underneath the weight of its cosmic hugeness. The harmonies are reminiscent of an earlier incarnation of the Byrds, and this is the reason it’s one of the latter-day (post-Notorious) songs I turn to most often…

Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde puts the rock back into the Byrds’ particular brand of country rock. The record is patchy and poorly recorded, with Bob Johnston’s thin, hollowed-out production value perhaps standing as an instance of incipient corporate rock, where craft becomes subordinate to efficient movement down the creative assembly line. It’s too bad because a slog through the record’s murkiness reveals, here and there, the amazing things that can happen with the interwoven guitar playing of Roger McGuinn and Clarence White. It seems to me that by now the Byrds were pretty much a live band. Their studio output from here on out doesn’t match the intensity of what they’re able to do on stage and in the moment. This is great if you like stretched-out live music. You’ll love every noodling second of the 15-minute all-instrumental rendition of Eight Miles High. But those of us who crave the precision, the artistry, and (hopefully) the attention to detail that studio recording affords will be a little leery. And yet, I come back to McGuinn and White. Their chemistry is electrifying. They really seem to relish being on stage together, an old folkie and a blue grass picker, completely simpatico in making rock that sounds huge and isn’t at all diminished by its country overtones. But having said all this, tonight’s song feels a bit nostalgic. You’ll never mistake it for pop, but the song has a folk-ish melodic structure that almost gets lost underneath the weight of its cosmic hugeness. The harmonies are reminiscent of an earlier incarnation of the Byrds, and this is the reason it’s one of the latter-day (post-Notorious) songs I turn to most often… Friday, August 31, 2012

byrdsongs, xxx

Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde puts the rock back into the Byrds’ particular brand of country rock. The record is patchy and poorly recorded, with Bob Johnston’s thin, hollowed-out production value perhaps standing as an instance of incipient corporate rock, where craft becomes subordinate to efficient movement down the creative assembly line. It’s too bad because a slog through the record’s murkiness reveals, here and there, the amazing things that can happen with the interwoven guitar playing of Roger McGuinn and Clarence White. It seems to me that by now the Byrds were pretty much a live band. Their studio output from here on out doesn’t match the intensity of what they’re able to do on stage and in the moment. This is great if you like stretched-out live music. You’ll love every noodling second of the 15-minute all-instrumental rendition of Eight Miles High. But those of us who crave the precision, the artistry, and (hopefully) the attention to detail that studio recording affords will be a little leery. And yet, I come back to McGuinn and White. Their chemistry is electrifying. They really seem to relish being on stage together, an old folkie and a blue grass picker, completely simpatico in making rock that sounds huge and isn’t at all diminished by its country overtones. But having said all this, tonight’s song feels a bit nostalgic. You’ll never mistake it for pop, but the song has a folk-ish melodic structure that almost gets lost underneath the weight of its cosmic hugeness. The harmonies are reminiscent of an earlier incarnation of the Byrds, and this is the reason it’s one of the latter-day (post-Notorious) songs I turn to most often…

Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde puts the rock back into the Byrds’ particular brand of country rock. The record is patchy and poorly recorded, with Bob Johnston’s thin, hollowed-out production value perhaps standing as an instance of incipient corporate rock, where craft becomes subordinate to efficient movement down the creative assembly line. It’s too bad because a slog through the record’s murkiness reveals, here and there, the amazing things that can happen with the interwoven guitar playing of Roger McGuinn and Clarence White. It seems to me that by now the Byrds were pretty much a live band. Their studio output from here on out doesn’t match the intensity of what they’re able to do on stage and in the moment. This is great if you like stretched-out live music. You’ll love every noodling second of the 15-minute all-instrumental rendition of Eight Miles High. But those of us who crave the precision, the artistry, and (hopefully) the attention to detail that studio recording affords will be a little leery. And yet, I come back to McGuinn and White. Their chemistry is electrifying. They really seem to relish being on stage together, an old folkie and a blue grass picker, completely simpatico in making rock that sounds huge and isn’t at all diminished by its country overtones. But having said all this, tonight’s song feels a bit nostalgic. You’ll never mistake it for pop, but the song has a folk-ish melodic structure that almost gets lost underneath the weight of its cosmic hugeness. The harmonies are reminiscent of an earlier incarnation of the Byrds, and this is the reason it’s one of the latter-day (post-Notorious) songs I turn to most often… Thursday, August 30, 2012

byrdsongs, xxix

On the thirty-first floor, a gold plated door, won't keep out the lord's burning rain... You don't have to be a country music lover to recognize Sin City as a moment of true inspiration. Think of it as Hollywood Babylon meets Hank Williams meets Raymond Chandler, with Sneaky Pete's pedal steel, languid and weepy, making the music feel as if it's pickled in a large jar of 'ludes. I must confess that the sedated LA cowboy thing – the lonely yet virile drifter, anesthetized against the horrors of napalm and Nixon, wandering the abandoned streets between Clark and Hilldale, taking up residence at the Ash Grove or the Troubadour, and maybe even joining a freaky cult out in Canoga Park – there’s times when I find it all very appealing even though it represents the death of something I cherish so deeply. I associate the drifter with the wolf king of LA, and with taking flight in the Astrodome, and with the Gary Lockwood character in Model Shop. But I’m sure the malaise I romanticize only looks good in retrospect. The hazy hangover was probably a bummer at the time, even before the Manson Family and Altamont threw the collapse of the California dream into such sharp relief. The time from JFK’s election to the Summer of Love, the very peak of human civilization (at least if you were white, he hastens to add), happened in the wink of an eye but also over several million light years. I can only imagine how disenchanting it must’ve been to have lived it and then still have it be fairly large in the rearview mirror, taunting a whole generation with its broken promises and its fading aftertaste of that split second of ecstasy...

I’m starting to sound like Jackson Browne. What can I say? I’m a dreamer, and a romantic, given to fits of pointless nostalgia. There’s not a week that goes by where I don’t think how great it would have been to have experienced LA in the 60s. But Sin City give me pause. Is it a song that's supposed to make LA seem attractive, a city of mystery, of celebratory decadence, of infinite potentiality? Or does it paint a picture of hell on earth, the ghastly fires of which will only be extinguished when the whole place finally slides into the Pacific?

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

byrdsongs, xxviii

I’m not a big Burritos guy, but I gotta admit that The Gilded Palace of Sin is pretty damn cosmic sounding. Sneeky Pete does what otherwise seems impossible in making the pedal steel sound psychedelic. And Hillman and Parsons replicate Everly Brothers-style harmonies in all their elfin strangeness, something nobody else has ever been able to do successfully, to my knowledge. …Released in early 1969, Gilded attempts to resolve some of the key tensions of the moment, and perhaps it’s its failure to do so that makes the music compelling. It’s a record that tries to be city and country, sophisticate and bumpkin, hippie and backwoodsman, modern and pre-modern, rock and country, and so on and so forth, choose your own binaries. The album takes things a step beyond Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which doesn’t try to resolve the tensions so much as it simply seeks to flee the disquietude of the 60s altogether. With Gilded, things are complicated by indecision. The desire to run away is still there, floating atop an idealization of rural simplicity, but the music also expresses a wish to keep one foot in the muck and mire. The music ends up sounding deeply conflicted. And this is not necessarily a bad thing. Notorious Byrd Brothers is also very conflicted sounding, but the the music coalesces around a dizzying effort to preserve pop as a viable art form. Gilded isn’t nearly as tragically heroic. The Burritos are merely trying to assimilate dueling tendencies into a coherent statement. They come close on a few songs, but the record as a whole tends to leave me feeling scattered and disoriented. Perhaps it couldn’t be otherwise. The music is a reflection of the muddled mindset of its time. But looking at the album now some 43 years after it first appeared, I see it as a vista point along the meandering march into boomer narcissism. The hippies will find out soon enough that one can’t simply run away and then have it both ways, being engaged and disengaged. And the disenchantment that comes with this realization will compel a deeper retreat into the self. The Flying Burrito Brothers, in other words, are not so far removed from those sensitive denizens of the canyons and passes, the troubadours of the Me Generation…

I’m not a big Burritos guy, but I gotta admit that The Gilded Palace of Sin is pretty damn cosmic sounding. Sneeky Pete does what otherwise seems impossible in making the pedal steel sound psychedelic. And Hillman and Parsons replicate Everly Brothers-style harmonies in all their elfin strangeness, something nobody else has ever been able to do successfully, to my knowledge. …Released in early 1969, Gilded attempts to resolve some of the key tensions of the moment, and perhaps it’s its failure to do so that makes the music compelling. It’s a record that tries to be city and country, sophisticate and bumpkin, hippie and backwoodsman, modern and pre-modern, rock and country, and so on and so forth, choose your own binaries. The album takes things a step beyond Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which doesn’t try to resolve the tensions so much as it simply seeks to flee the disquietude of the 60s altogether. With Gilded, things are complicated by indecision. The desire to run away is still there, floating atop an idealization of rural simplicity, but the music also expresses a wish to keep one foot in the muck and mire. The music ends up sounding deeply conflicted. And this is not necessarily a bad thing. Notorious Byrd Brothers is also very conflicted sounding, but the the music coalesces around a dizzying effort to preserve pop as a viable art form. Gilded isn’t nearly as tragically heroic. The Burritos are merely trying to assimilate dueling tendencies into a coherent statement. They come close on a few songs, but the record as a whole tends to leave me feeling scattered and disoriented. Perhaps it couldn’t be otherwise. The music is a reflection of the muddled mindset of its time. But looking at the album now some 43 years after it first appeared, I see it as a vista point along the meandering march into boomer narcissism. The hippies will find out soon enough that one can’t simply run away and then have it both ways, being engaged and disengaged. And the disenchantment that comes with this realization will compel a deeper retreat into the self. The Flying Burrito Brothers, in other words, are not so far removed from those sensitive denizens of the canyons and passes, the troubadours of the Me Generation…Tuesday, August 28, 2012

jingle jangle mornings, seven

I like those pop life moments when the student becomes the teacher, and vice versa. The Everly Brothers’ much underappreciated Two Yanks in England, featuring the Hollies as their backing players, is a case in point. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that there would not have been a British Invasion in the absence of the Everly Brothers, or at least the British Invasion would not have been what it was. The Everlys' sound and melodic structures exerted an enormous influence over Merseybeat in particular. But by the mid 60s, they were unable to transition into the new order of things and became an unhip relic of a more innocent time. In 1966 they attempted resuscitate their flagging career, setting out to make a record that sounded like a fusion of folk rock and the British Invasion. Unfortunately, Two Yanks in England, recorded at the legendary Pye Studios in London, was about six months behind the curve and failed to do much business. Why would any self-respecting kid with her finger on the pulse of cool things wanna hear the Everlys trying to be hip, a hipness once removed, when much more authentic sounding records were hitting the shelves virtually every day? But this doesn't mean that Two Yanks doesn't sound great now. Tonight's song deserves to be at least a cult classic. ...Interestingly enough, the Everlys made another attempt to become hip in the late 60s with the country rock flavored Roots. Maybe tomorrow I'll post one from Roots if anything's available. Both records are ones where things have come full circle. Usually this only happens once, if at all, which only goes to show how deeply influential Phil and Don were...

byrdsongs, xxvii

Chris Hillman left the Byrds after the release of Sweetheart of the Rodeo in the summer of 1968. Although dissatisfaction with the band’s management was the immediate impetus for his departure, I’ve gotten the sense in looking at his career and reading as much as I can that country and bluegrass were always his first loves, and this is how I frame his decision to join forces with Gram Parsons in forming the Flying Burrito Brothers. Parsons was much more of a country purist than McGuinn, and I think Hillman was restless and looking for a way to follow his bliss. Meanwhile, McGuinn chose to soldier on under the banner of the Byrds, the sole remaining member of the original cast. Hillman and Parsons asked Clarence White to join them in the Burritos, but White opted to become a full-time member of the Byrds. He’d been playing Byrds sessions going back to Younger than Yesterday and said in an interview that he’d always wanted to be in the band…

The interplay between White and McGuinn is, for me, what puts the post-Hillman Byrds several steps above the other country rock acts of the era. Here you have two of the greatest guitarists ever in the same band. White seems to have recognized that the Byrds were McGuinn’s band. His playing never draws too much attention to itself, though there are certainly moments when he unleashes incredible, c&w-infused solos. He was also, in the southern tradition, a humble gentleman on stage, remaining calm and restrained, content to be an accompanist for the most part but doing so much more when the music called for it. Something about the frame of mind of bluegrass pickers who became rock guitarists – I’m thinking here not only of White but also of White’s good friend and admirer, Captain Trips – leads them to comport themselves with gentle humility on stage. They don’t have to blow your mind with all kinds of extra-musical antics, instead letting their playing speak for itself. I like that. There’s room for theatricality in rock 'n roll, no doubt, but there’s also something cool about simply allowing the music be the central focus. This is not to say that Clarence White was devoid of panache. The white Nudie suits he’d eventually wear on stage were very stylish and gave the Byrds a cosmic cowboy aura…

Tonight’s performance is from an episode of the great teevee program, Playboy After Dark, taped in late 1968. Bob Dylan’s songbook is a source of continuity amidst a completely transformed band that features, along with White and McGuinn, John York on bass and either (I can’t tell) Gene Parsons (no relation to Gram) or Kevin Kelley on drums. You Ain’t Goin Nowhere had already been covered on Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and a version of This Wheel’s on Fire would eventually be the stunning album opener on Dr Byrds and Mr Hyde. The Band’s cover of the latter song would become more well-known because Music From Big Pink was one of the great cultural events of the late 60s. But the Byrds’ version, with its incredible wall of guitar noise, is by far the better of the two. The original versions of both songs performed in this clip eventually showed up on what became known as Dylan’s Basement Tapes, but back in 1968 you had to work pretty hard to hear them. Scratchy bootleg tapes made the rounds among Dylan acolytes, and tonight’s clip will make you glad they did…

Tonight’s performance is from an episode of the great teevee program, Playboy After Dark, taped in late 1968. Bob Dylan’s songbook is a source of continuity amidst a completely transformed band that features, along with White and McGuinn, John York on bass and either (I can’t tell) Gene Parsons (no relation to Gram) or Kevin Kelley on drums. You Ain’t Goin Nowhere had already been covered on Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and a version of This Wheel’s on Fire would eventually be the stunning album opener on Dr Byrds and Mr Hyde. The Band’s cover of the latter song would become more well-known because Music From Big Pink was one of the great cultural events of the late 60s. But the Byrds’ version, with its incredible wall of guitar noise, is by far the better of the two. The original versions of both songs performed in this clip eventually showed up on what became known as Dylan’s Basement Tapes, but back in 1968 you had to work pretty hard to hear them. Scratchy bootleg tapes made the rounds among Dylan acolytes, and tonight’s clip will make you glad they did… Monday, August 27, 2012

jingle jangle mornings, six

To the extent that the 13th Floor Elevators are remembered at all, it’s by a small handful of cultists, of which I include myself. They’re not really thought of as a jangle band. I’d call them a blues-based, psychedelic jug band. (I like to be precise). But they did have a few poppy songs with ringing guitars, like the one I’ve posted tonight… The Elevators’ records were poorly recorded, even by the standards of psychedelic-era garage bands. But the amateurishness of the recording and sound is part of the charm, and there’s an irresistible Frisco-via-Texas strangeness that pops and crackles just beneath the surface of things. Listen carefully because there’s a lot more going on than you’re likely to notice with your attention divided. Rocky Erickson, a mercurial front man if ever there was one, is the main source of the band’s freaky energy, and when his voice laid over guitars that buzz and chime, it’s hard not to fall under the spell of this music’s hallucinogenic groove…

To the extent that the 13th Floor Elevators are remembered at all, it’s by a small handful of cultists, of which I include myself. They’re not really thought of as a jangle band. I’d call them a blues-based, psychedelic jug band. (I like to be precise). But they did have a few poppy songs with ringing guitars, like the one I’ve posted tonight… The Elevators’ records were poorly recorded, even by the standards of psychedelic-era garage bands. But the amateurishness of the recording and sound is part of the charm, and there’s an irresistible Frisco-via-Texas strangeness that pops and crackles just beneath the surface of things. Listen carefully because there’s a lot more going on than you’re likely to notice with your attention divided. Rocky Erickson, a mercurial front man if ever there was one, is the main source of the band’s freaky energy, and when his voice laid over guitars that buzz and chime, it’s hard not to fall under the spell of this music’s hallucinogenic groove…byrdsongs, xxvi

Los Angeles became the main incubation space for country rock for a number of reasons. For one thing, the city is quite literally the outer edge of the western frontier, and as such it has always fed into the explorer/cowboy archetype. You may be sitting in horrible traffic on the Golden State Freeway, but it still somehow feels like the Wild West out here. Even in the second half of the 20th century, as rapacious developers went on a rampage, gobbling up every last bit of available land and overbuilding the region beyond sustainability, the dispersed spatial topography of LA continued to give it an expansive feel that fed right into the mythic American motifs that were a key source of inspiration for country rock. And then there's the natural terrain and its fusion with urban life. Angelenos of a certain age will remember the way the late Jerry Dunphy used to sign off his news cast: 'From the desert to the sea to all of Southern California…' He could have thrown in the mountains as well. The intensity of nature is part of the daily lived experience here, and I’ve always felt that this, as much as anything, is the source of the West Coast sound. When people refer to West Coast harmonies, what they really mean is Los Angeles harmonies. It starts with the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean and curls its way up through the Mamas and the Papas, the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, and then finds its fullest expression in Crosby Stills and Nash. For all the reservations I have about CSN, the sheer perfection of their harmonies ties them inseparably to LA, and this redeems them for me... The awesome power of nature – pleasing, angry, sublime, terrifying, – is reflected in the otherworldly blending of voices, flawless multi-part harmonies that make you stop what you’re doing and pay attention. It hits you on a spiritual level. And harmonies are such an important part of country music. This is another reason why Los Angeles was so hospitable to country rock. Just listen to the harmonies in tonight’s song. Where else could music like that possibly come from? It’s pop…It’s c&w…It’s harmony…It’s life beating Gene Clark down, but it’s also Gene Clark living another day to tell about it, with a little help from his friends. The music is as beautiful as the place that inspired it...

Los Angeles became the main incubation space for country rock for a number of reasons. For one thing, the city is quite literally the outer edge of the western frontier, and as such it has always fed into the explorer/cowboy archetype. You may be sitting in horrible traffic on the Golden State Freeway, but it still somehow feels like the Wild West out here. Even in the second half of the 20th century, as rapacious developers went on a rampage, gobbling up every last bit of available land and overbuilding the region beyond sustainability, the dispersed spatial topography of LA continued to give it an expansive feel that fed right into the mythic American motifs that were a key source of inspiration for country rock. And then there's the natural terrain and its fusion with urban life. Angelenos of a certain age will remember the way the late Jerry Dunphy used to sign off his news cast: 'From the desert to the sea to all of Southern California…' He could have thrown in the mountains as well. The intensity of nature is part of the daily lived experience here, and I’ve always felt that this, as much as anything, is the source of the West Coast sound. When people refer to West Coast harmonies, what they really mean is Los Angeles harmonies. It starts with the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean and curls its way up through the Mamas and the Papas, the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, and then finds its fullest expression in Crosby Stills and Nash. For all the reservations I have about CSN, the sheer perfection of their harmonies ties them inseparably to LA, and this redeems them for me... The awesome power of nature – pleasing, angry, sublime, terrifying, – is reflected in the otherworldly blending of voices, flawless multi-part harmonies that make you stop what you’re doing and pay attention. It hits you on a spiritual level. And harmonies are such an important part of country music. This is another reason why Los Angeles was so hospitable to country rock. Just listen to the harmonies in tonight’s song. Where else could music like that possibly come from? It’s pop…It’s c&w…It’s harmony…It’s life beating Gene Clark down, but it’s also Gene Clark living another day to tell about it, with a little help from his friends. The music is as beautiful as the place that inspired it...Sunday, August 26, 2012

byrdsongs, xxv

The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard and Clark is my favorite country rock record. But 'country rock' is not really a good description for what's on offer here. It's more like country pop, with Gene Clark's penchant for two-minute romantic tragedies entwined with Doug Dillard's bluegrass textures. The ensemble cast of backing players from in and around the Byrds' orbit - folks like Clarence White, Chris Hillman, Bernie Leadon, and Sneaky Pete Kleinow - give the record a vibe that's traditional sounding enough but never veers into purist territory, and for this I'm thankful. As with so many things Clark was involved in after the Byrds, it's a shame that Fantastic Expedition was a commercial failure. The record is what country rock should be - charming, catchy, accessible, and light. Today's song is Gene Clark doing what he does best and features lovely strings arranged by Van Dyke Parks.I believe it was released as a single at or around the time of Fantastic Expedition and only subsequently was added to the album as a bonus track. No matter. After the first few listens, I bet you'll be singing along with the chorus. How does one make heartbreak sound so joyful?

Saturday, August 25, 2012

jingle jangle mornings, five

The West Coat Pop Art Experimental Band are one of the great lost bands of Hollywood's Mondo Mod era. If you like your ethereal jangle pop with an extra teaspoon of weird, these guys are for you. Transparent Day is a composite of everything I want in my pop music, the British Invasion filtered through the Sunset Strip at its shimmering highpoint. The harpsichord in the bridge adds a nice baroque flavor to things, and the harmonies are about as dreamy as you can get outside of the Mamas and the Papas. But it's really the guitars, ringing out so cleanly and so clearly, that'll have you coming back for more. I wish this kind of stuff came in a bottle because then every day would be transparent, and what a delightful world we'd be living in...

Friday, August 24, 2012

byrdsongs, xxiv

I guess what I was trying to say in my last post is that, if I’d just months earlier had my mind completely blown by The Notorious Byrd Brothers, a creative peak not just for the Byrds but for pop music as an art form, I think Sweetheart of the Rodeo would be a downer for me. Luckily we don’t have to listen to these records in chronological order. Sweetheart can now be appreciated outside of its historical context as a very good country music record, with a few nods to rock ‘n roll here and there. The song I’ve posted today, a real high plains drifter of a tune, is my favorite on the album. The pedal steel playing makes things canter along at a nice relaxed pace, giving off rustic good vibes along the way… For all its greatness, I wouldn’t characterize the Notorious Byrd Brothers as a relaxing album. It’s fucking intense. It’s not music I put on when I’m folding the laundry or washing dishes. It requires your full attention. I play it when I want to be moved spiritually, intellectually, viscerally. Sweetheart is done with all that. It reflects a desire to go back to a place where things are simple, everything’s done on a first-name basis, and time stands still. And you know what? If I let my guard down and allow myself to go where Sweetheart wants to take me, I understand its appeal. There’s something very attractive about trying to extricate oneself from the complex vagaries of modernity. It’s the allure of Jeffersonian Democracy, a nation of farmers and small shopkeepers living in a transparent world of their own making. Sweetheart makes a wish for this way of life. I know that the wish is a fantasy, at least in the post-industrial world, but when I’m in the right frame of mind, relaxed and free of worry, I can give myself over to it for a few moments...

I guess what I was trying to say in my last post is that, if I’d just months earlier had my mind completely blown by The Notorious Byrd Brothers, a creative peak not just for the Byrds but for pop music as an art form, I think Sweetheart of the Rodeo would be a downer for me. Luckily we don’t have to listen to these records in chronological order. Sweetheart can now be appreciated outside of its historical context as a very good country music record, with a few nods to rock ‘n roll here and there. The song I’ve posted today, a real high plains drifter of a tune, is my favorite on the album. The pedal steel playing makes things canter along at a nice relaxed pace, giving off rustic good vibes along the way… For all its greatness, I wouldn’t characterize the Notorious Byrd Brothers as a relaxing album. It’s fucking intense. It’s not music I put on when I’m folding the laundry or washing dishes. It requires your full attention. I play it when I want to be moved spiritually, intellectually, viscerally. Sweetheart is done with all that. It reflects a desire to go back to a place where things are simple, everything’s done on a first-name basis, and time stands still. And you know what? If I let my guard down and allow myself to go where Sweetheart wants to take me, I understand its appeal. There’s something very attractive about trying to extricate oneself from the complex vagaries of modernity. It’s the allure of Jeffersonian Democracy, a nation of farmers and small shopkeepers living in a transparent world of their own making. Sweetheart makes a wish for this way of life. I know that the wish is a fantasy, at least in the post-industrial world, but when I’m in the right frame of mind, relaxed and free of worry, I can give myself over to it for a few moments...Thursday, August 23, 2012

byrdsongs xxiii

A reader responded to one of my posts from a few days ago, asking me why I hate Sweetheart of the Rodeo. I’m sorry if I gave this impression. I don’t hate it at all. It’s a very well played record. The songs are good. It’s just not my cup of tea. I’m about as far from being a country music purist as one can be, and Sweetheart strikes me as being a purist endeavor. This assessment is, of course, only relative to my taste. A real purist will tell you that Sweetheart is a rock ‘n roll record and not worth the time of day. At the time, many were not happy that the Byrds were allowed to play the Grand ‘Ol Opry. Subsequent Byrds albums remained in the orbit of c&w but were fused with rock much more liberally. Plus, Clarence White became an official member of the band starting with Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde, and even though he came from a country and bluegrass tradition, his playing is so dazzling, more than enough to make me forget all my reservations about country music…

A reader responded to one of my posts from a few days ago, asking me why I hate Sweetheart of the Rodeo. I’m sorry if I gave this impression. I don’t hate it at all. It’s a very well played record. The songs are good. It’s just not my cup of tea. I’m about as far from being a country music purist as one can be, and Sweetheart strikes me as being a purist endeavor. This assessment is, of course, only relative to my taste. A real purist will tell you that Sweetheart is a rock ‘n roll record and not worth the time of day. At the time, many were not happy that the Byrds were allowed to play the Grand ‘Ol Opry. Subsequent Byrds albums remained in the orbit of c&w but were fused with rock much more liberally. Plus, Clarence White became an official member of the band starting with Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde, and even though he came from a country and bluegrass tradition, his playing is so dazzling, more than enough to make me forget all my reservations about country music… It’s not accurate to say that I dislike Sweetheart, but I don’t really see it as a Byrds record. To me, it sounds like a Gram Parsons record with the Byrds as his backing band. I know that's unfair, but I think he was the dominant figure on Sweetheart, and this is quite likely the reason his tenure with the Byrds was so short. ...People will disagree with me when I say this, but Gram Parsons was a purist. He may have had a rock ‘n roll heart, but his first love was always country music. Even the Flying Burrito Brothers feel too pure for me, though they’re redeemed by scattered rock ‘n roll breathing spells.

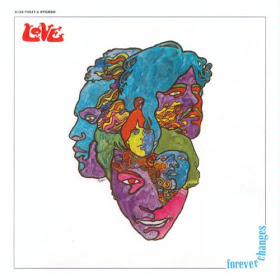

It’s not accurate to say that I dislike Sweetheart, but I don’t really see it as a Byrds record. To me, it sounds like a Gram Parsons record with the Byrds as his backing band. I know that's unfair, but I think he was the dominant figure on Sweetheart, and this is quite likely the reason his tenure with the Byrds was so short. ...People will disagree with me when I say this, but Gram Parsons was a purist. He may have had a rock ‘n roll heart, but his first love was always country music. Even the Flying Burrito Brothers feel too pure for me, though they’re redeemed by scattered rock ‘n roll breathing spells. Let me put it this way: I imagine myself growing up in Los Angeles and being a senior at UCLA in 1967. Let's say I’m a huge Byrds obsessive. I’ve seen them play at Ciro’s Le Disc and other places on the Strip. Now the cops have shut most of that down. Let's say that I participated in the demonstrations and got my head cracked open. I can feel things changing, and I’m pretty sure I don’t like where it’s all going. The freedom of innocence seems to be receding. I wonder where all the fun has gone. I wonder if listening to Sgt. Pepper and going to Monterey last summer will end up being the last time any of us had any fun… New Year's day comes and goes. On a cool evening in February, I make the trek from campus to Music City in Hollywood. I see The Notorious Byrd Brothers in the window. I scrape enough out of my pockets to buy it even though I’m a starving student. It’s a new Byrds record, and I have to have it. I even find the money to also purchase Forever Changes, the latest from my other favorite group...

I take the LPs back to my dorm. I gather a few friends from down the hall. We pass around a reefer and listen intently. We’re stunned by what we hear. The music seems so in tune with everything that’s going on. The songs are catchy and poignant and perfect. God I love the Byrds! How do you make music this good? It’s perfectly self-contained, and concise, and infectious, and life affirming! Notorious is everything I want music to be…

Fast forward to the red hot summer of '68... The sping was bad enough. But things are worsening. The pace of deterioration is picking up. A high school friend of mine comes home from Viet Nam in a box. Now more than ever, I need music to keep me from going mad with sadness and fear and anger. Another Byrds album comes out. I remember how The Notorious Byrd Brothers made me feel. It still makes me feel this way. I crave that feeling, something to hang on to. Back at the record shop, I see Sweetheart of the Rodeo in the window. It’s got a drawing of a cowgirl on the cover. The artwork and title make me uneasy. You can’t judge a book by its cover, but we always do anyway, and this one looks like it’s gonna be different somehow. There have been flashes of country music on the last few Byrds records, but it’s always subtly integrated into their distinct sound. I take the record home. As I remove the LP from its wrapping, I have a moment of insight. Is it even possible to make music like the Byrds have made anymore? Can a world that’s become so ugly possibly nurture such beautiful sounds? I already know the answer to this question, but I savor that final instant of hope before the needle touches vinyl…

Fast forward to the red hot summer of '68... The sping was bad enough. But things are worsening. The pace of deterioration is picking up. A high school friend of mine comes home from Viet Nam in a box. Now more than ever, I need music to keep me from going mad with sadness and fear and anger. Another Byrds album comes out. I remember how The Notorious Byrd Brothers made me feel. It still makes me feel this way. I crave that feeling, something to hang on to. Back at the record shop, I see Sweetheart of the Rodeo in the window. It’s got a drawing of a cowgirl on the cover. The artwork and title make me uneasy. You can’t judge a book by its cover, but we always do anyway, and this one looks like it’s gonna be different somehow. There have been flashes of country music on the last few Byrds records, but it’s always subtly integrated into their distinct sound. I take the record home. As I remove the LP from its wrapping, I have a moment of insight. Is it even possible to make music like the Byrds have made anymore? Can a world that’s become so ugly possibly nurture such beautiful sounds? I already know the answer to this question, but I savor that final instant of hope before the needle touches vinyl…Wednesday, August 22, 2012

burdsongs, xxii

Change is Now is the most explicit statement on The Notorious Byrd Brothers of the record's moment in time. Things that seem to be solid are not. The song moves from folk rock to c&w to full-on acid raga, and back again, all in less than three and a half minutes. What I hear in the song, with the benefit of more than four decades hindsight, is that things went from this to this to this because of this and this and this. The pensive Beatles-ish chord that brings things to a close makes me want to close my eyes and raise my face to the warm rays of the California sun. And that’s the thing. For all the internal and external discord and tumult that is the music’s condition of possibility, the message and vibe are strangely optimistic. Dance to the day when fear it is gone. You’d never guess at the time that a radical retreat was only months away. I suppose imminent death or collapse breeds bravery as one comes to the realization that there’s nothing left to lose… The raga break - achieved, I believe, with a heavily flanged guitar and an early use of moog synthesizer, as well as Hillman’s super-heavy yet agile bass playing – is at once lurid, beautiful, terrifying, pleasing and disturbing, like a B-52 making the most gorgeous sounds you’ve ever heard. To experience the full magnificence of this song, I recommend hearing it through a set of cans and playing it maximum volume...

Change is Now is the most explicit statement on The Notorious Byrd Brothers of the record's moment in time. Things that seem to be solid are not. The song moves from folk rock to c&w to full-on acid raga, and back again, all in less than three and a half minutes. What I hear in the song, with the benefit of more than four decades hindsight, is that things went from this to this to this because of this and this and this. The pensive Beatles-ish chord that brings things to a close makes me want to close my eyes and raise my face to the warm rays of the California sun. And that’s the thing. For all the internal and external discord and tumult that is the music’s condition of possibility, the message and vibe are strangely optimistic. Dance to the day when fear it is gone. You’d never guess at the time that a radical retreat was only months away. I suppose imminent death or collapse breeds bravery as one comes to the realization that there’s nothing left to lose… The raga break - achieved, I believe, with a heavily flanged guitar and an early use of moog synthesizer, as well as Hillman’s super-heavy yet agile bass playing – is at once lurid, beautiful, terrifying, pleasing and disturbing, like a B-52 making the most gorgeous sounds you’ve ever heard. To experience the full magnificence of this song, I recommend hearing it through a set of cans and playing it maximum volume...Tuesday, August 21, 2012

byrdsongs, xxi

The second Goffin and King track on Notorious Byrd Brothers, Wasn’t Born to Follow, is what I wish country rock had become. The song’s little two-step giddyup gives it an obvious c&w vibe, but the flanged guitars make the song feel trippy in a way that’s almost entirely absent from what would soon come from the Flying Burrito Brothers, Poco, and even most of what the Byrds did in the post-Notorious era. There’s a reason Wasn’t Born to Follow works so beautifully in Easy Rider. This is music for a motorcycle, an iron horse as opposed to flesh and blood. Mechanization, modern and complex, still remains on par here with the simpler pleasures of the mythic agrarian past, but only for the time being, and only tenuously. An impulse to flee into the arms of Mother Nature is built into the song and is something it shares with more typically rustic sounding country rock. Where the trees have leaves of prisms, and break the light in colors, that no one knows the names of. But the Byrds aren’t quite ready to leave the city behind. I mentioned how Notorious is a record that feels like it’s trying to avoid complete capitulation. Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which, staggeringly, comes a mere seven months later, is music of resignation. Notorious is still straddling things, and the pull between the past/present and the present/future is the source of the record’s eclectic brilliance. Wasn’t Born to follow is the perfect crystallization of this creative tension, transforming it into a two-minute sound collage that’s as coherent as it is sublime…

The second Goffin and King track on Notorious Byrd Brothers, Wasn’t Born to Follow, is what I wish country rock had become. The song’s little two-step giddyup gives it an obvious c&w vibe, but the flanged guitars make the song feel trippy in a way that’s almost entirely absent from what would soon come from the Flying Burrito Brothers, Poco, and even most of what the Byrds did in the post-Notorious era. There’s a reason Wasn’t Born to Follow works so beautifully in Easy Rider. This is music for a motorcycle, an iron horse as opposed to flesh and blood. Mechanization, modern and complex, still remains on par here with the simpler pleasures of the mythic agrarian past, but only for the time being, and only tenuously. An impulse to flee into the arms of Mother Nature is built into the song and is something it shares with more typically rustic sounding country rock. Where the trees have leaves of prisms, and break the light in colors, that no one knows the names of. But the Byrds aren’t quite ready to leave the city behind. I mentioned how Notorious is a record that feels like it’s trying to avoid complete capitulation. Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which, staggeringly, comes a mere seven months later, is music of resignation. Notorious is still straddling things, and the pull between the past/present and the present/future is the source of the record’s eclectic brilliance. Wasn’t Born to follow is the perfect crystallization of this creative tension, transforming it into a two-minute sound collage that’s as coherent as it is sublime…Monday, August 20, 2012

byrdsongs, xx

You may have gathered from my musings over time that I’m obsessed with Tin Pan Alley, and really songwriters more generally. I think it’s part of that unseen / under- appreciated hero fetish of mine. Songwriters whose words and music propel pop idols to superstardom…the session players who play the music but remain largely hidden in the shadows…the producers who barely get a mention in small typeface on the back of the LP…all the indispensable people who make it happen while flying under the radar. Nowadays there’s so much more readily-accessible information available to even those with only a passing interest in knowing who did what on which record. It’s easy to forget, for example, that at the height of the Brill Building’s productivity, most of the writers and musicians manufacturing the hits labored in relative obscurity...

You may have gathered from my musings over time that I’m obsessed with Tin Pan Alley, and really songwriters more generally. I think it’s part of that unseen / under- appreciated hero fetish of mine. Songwriters whose words and music propel pop idols to superstardom…the session players who play the music but remain largely hidden in the shadows…the producers who barely get a mention in small typeface on the back of the LP…all the indispensable people who make it happen while flying under the radar. Nowadays there’s so much more readily-accessible information available to even those with only a passing interest in knowing who did what on which record. It’s easy to forget, for example, that at the height of the Brill Building’s productivity, most of the writers and musicians manufacturing the hits labored in relative obscurity... Which brings me back to the Byrds, and to The Notorious Byrd Brothers. The record features two great songs by the Tin Pan Alley songwriting team of Gerry Goffin and Carole King, who were best known at the time for having penned Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow, arguably the high-water mark of the Golden Age of Rock ‘n Roll. But by the late 60s, the Brill Building was decidedly unhip. Hippies preferred 20-minute drum solos over two-minute teenage symphonies to god. But the two Goffin and King songs on Notorious are stunning. Much of their greatness is simply that the lyrics are poignant and the melodies are lovely. But you also have to give a lot of credit to McGuinn and Hillman for the performances, and to producer Gary Usher, who pulls all the elements together and makes each song into a mini-masterpiece…

Which brings me back to the Byrds, and to The Notorious Byrd Brothers. The record features two great songs by the Tin Pan Alley songwriting team of Gerry Goffin and Carole King, who were best known at the time for having penned Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow, arguably the high-water mark of the Golden Age of Rock ‘n Roll. But by the late 60s, the Brill Building was decidedly unhip. Hippies preferred 20-minute drum solos over two-minute teenage symphonies to god. But the two Goffin and King songs on Notorious are stunning. Much of their greatness is simply that the lyrics are poignant and the melodies are lovely. But you also have to give a lot of credit to McGuinn and Hillman for the performances, and to producer Gary Usher, who pulls all the elements together and makes each song into a mini-masterpiece…

Notorious opens with McGuinn and Hillman’s Artificial Energy, a song about uppers with a narrative that ends with the protagonist either killing the actual queen (but of what we don’t know) or killing “a queen,” as in a homosexual, under drug-fueled circumstances that are left to the imagination. The song’s bad-trip vibe is made even more raw and striking by the raucous R&B-flavored arrangement, replete with horns-a-go-go, and a fade out that forces you to experience the come down. Then comes the first of the two Goffin and King songs, Goin’ Back, a wistful ode to the innocence of childhood that couldn’t be more stark in its juxtaposition with the speedy freak out of Artificial Energy. Within its time and place, Goin’ Back also represents a recognition that the teen paradise of the mid 60s is turning into something much darker. With its interplay of glockenspiel, pedal steel, and McGuinn’s butterfly guitar flourishes, the song makes you feel like you’re walking in a pleasant dream. There’s nothing to clutter your mind. Everything's beautiful, nothing hurts. And as the song fades and those angelic voices caress your face like warm mist, you might even have a moment or two feeling as if you were back in the womb…

Sunday, August 19, 2012

byrdsongs, xix

The Notorious Byrd Brothers, recorded in sporadic episodes during the second half of 1967 and released in January of '68, is an incredibly heady LP, the Byrds' last as a pop band and, for me anyway, their very best. Along with Smile and Revolver, Notorious is the definitive expression of what pop can be. All three records are at the outer limits of a creative threshold, arriving at a potent intersection where artistic daring and mind expansion collide with the combustible social forces in play at the time. All three records also appropriate elements of rock, attempting to make statements of conceptual depth and doing so with a more assertive, 'heavier' sound, and in this sense none of them can be viewed as pure pop records. This is especially so for Notorious... The passage from pop to rock reflects social devolution, but the rock aspects of Notorious don't at all diminish its power. Quite the contrary. Remember that Notorious is about a year later than Smile and Revolver, and perhaps this explains the urgency of its vibe. The music feels like it's trying to hang on to a simpler world while knowing that time won't yield for anyone or anything. Every time I hear it, I find myself wanting to hang on as well, which makes the listening experience that much more poignant because I have the benefit, so to speak, of knowing what happened next... It's a tragedy that Smile never saw the light of day and that Notorious was a commercial flop. Revolver is of course another story... The Byrds were fraying amidst the making of Notorious. First Crosby was fired and then Michael Clarke left the band, reducing the group for a short while to McGuinn, Hillman and some session players, including Clarence White, Jim Gordon, and Hal Blaine. In spite of his departure, Notorious features some excellent Crosby songs, including Dolphin's Smile, Tribal Gathering and, most of all, Draft Morning, which I've posted for today. Listen for Hillman's chilling mandolin in the verse, along with his heavier than heavy bass playing and the Sgt. Pepper-style horns/mellotron in the song's spectacular bridge. All of these are elements of rock, and I'm ok with them. The first flushes of rock simply mean that the music has a slightly harder sound. Notorious never gives itself over completely to the heaviness. I give producer Gary Usher credit for this. He's the real hero of Notorious, managing to make the record sound huge without ever making it feel swollen. It's just perfect, for one last time...

Friday, August 17, 2012

byrdsongs, xviii

A break with David Crosby was only a matter of time after the Summer of Love. There’s the matter of his JFK rant at Monterey Pop. He wasn’t wrong in what he said, but one gets the sense that he was almost a parody, the kind of arm chair rebel whose idea of being radical is letting his freak flag fly.

A break with David Crosby was only a matter of time after the Summer of Love. There’s the matter of his JFK rant at Monterey Pop. He wasn’t wrong in what he said, but one gets the sense that he was almost a parody, the kind of arm chair rebel whose idea of being radical is letting his freak flag fly. And then there’s the slow simmer of tension within the Byrds. My impression of Jim McGuinn, who changed his name to Roger around this time after getting into Subud, is that he was a bit conservative and quite possibly prudish as well. This is only a guess based on things I’ve inferred from interviews, articles, and books. By ‘conservative’ I don’t mean right wing but rather that he was/is, at heart, a serious folk musician. And you know what those serious folk guys are like. They’re almost as bad as jazzholes. They don’t like any shenanigans served with their music. McGuinn says he was not a folk purist and I believe him because, after all, he plugged in, which for the purists was sacrilege. But this doesn’t mean he wasn’t serious, and this kind of seriousness was anathema to Crosby’s act at the time. I can see why McGuinn would come to resent Crosby, someone who made such an effort to draw attention to himself as opposed to drawing it to the music. It’s not hard to imagine how McGuinn reacted when Crosby came to the guys with Triad, which is so much more than just a ménage a trois song. It calls monogamy into question, makes a mockery of it, in fact. It’s thrilling to hear the Byrds’ version of the song, but it’s a cheap thrill. Where Lady Friend is a high point for pop as a vital force in the culture, Triad indicates that the patient has become irretrievably sick. The song is a fever dream.

And then there’s the slow simmer of tension within the Byrds. My impression of Jim McGuinn, who changed his name to Roger around this time after getting into Subud, is that he was a bit conservative and quite possibly prudish as well. This is only a guess based on things I’ve inferred from interviews, articles, and books. By ‘conservative’ I don’t mean right wing but rather that he was/is, at heart, a serious folk musician. And you know what those serious folk guys are like. They’re almost as bad as jazzholes. They don’t like any shenanigans served with their music. McGuinn says he was not a folk purist and I believe him because, after all, he plugged in, which for the purists was sacrilege. But this doesn’t mean he wasn’t serious, and this kind of seriousness was anathema to Crosby’s act at the time. I can see why McGuinn would come to resent Crosby, someone who made such an effort to draw attention to himself as opposed to drawing it to the music. It’s not hard to imagine how McGuinn reacted when Crosby came to the guys with Triad, which is so much more than just a ménage a trois song. It calls monogamy into question, makes a mockery of it, in fact. It’s thrilling to hear the Byrds’ version of the song, but it’s a cheap thrill. Where Lady Friend is a high point for pop as a vital force in the culture, Triad indicates that the patient has become irretrievably sick. The song is a fever dream.

McGuinn (and presumably Hillman as well) vetoed Triad for inclusion on The Notorious Byrd Brothers, and after they fired Crosby from the Byrds, Crosby offered the song to the Jefferson Airplane, who gave it a bombastic Slouching Towards Bethlehem-ish interpretation, their stock in trade after Marty Balin’s position in the band was marginalized. The Byrds original version of Triad is groovier, and it's more subtle, no mean feat given Crosby’s outsized self-concept. Listening to the song fills me with a strange combination of admiration and contempt…

Thursday, August 16, 2012

byrdsongs, xvii

Lady Friend is not only the best thing David Crosby did with the Byrds but is the finest song of his career. It’s certainly one of my three or four favorite byrdsongs, though it can really be viewed as a David Crosby solo performance, Crosby having re-recorded his own harmony ovberdubs in place of McGuinn and Hillman’s initial backing vocals. McGuinn and Hillman are more or less reduced to being session players… As hard as it is to like Crosby the man, there’s no denying his massive talent as a vocalist, and he had some pretty good pop instincts as well, which are easily overlooked due to his much higher profile in Crosby Stills and Nash, where the whole point was to (d)evolve from the lightness of pop to the overwrought self-righteousness of corporate hippy rock. I don’t dislike CSN. They made a lot of good music and occupied a big place in my childhood. On a personal level, they make me think of the hours and hours I spent alone in my room as a kid. It’s not always a set of memories I want to return to, but they definitely made me feel less alone back then. It still blows my mind when I think of CSN as essentially the Byrds + Buffalo Springfield + the Hollies. The thing is, though, I’ll take any one of those three bands over CSN any day of the week. Even with CSN’s unmatched harmonies, they just sound too serious about themselves for my taste. I didn’t recognize this about them when I was little, or if I did I interpreted it as cool hippy earnestness, something to emulate. We get more jaded and cynical as we age and nowadays CSN strike me as a symbol of everything that went wrong in the late 60s. Even their vaunted harmonies sound shrill to me now, exquisitely executed and oh so heavy handed... Lady Friend was Crosby’s last stab at the pop life. He went about it using the Gene Clark Happy/Sad song formula and added a lovely orchestral sheen. I’m not sure who arranged the horns. I tend to be suspicious of horns and really anything that makes guitars harder to hear, but the horns in Lady Friend really elevate the song into the realm of great pop art. Crosby’s two other masterpieces from this period, Draft Morning and Triad, are really pop/rock hybrids. They’re terrific songs, but they lack Lady Friend’s pop purity. …Crosby was apparently unhappy with the way Gary Usher mixed Lady Friend. It’s admittedly a bit muddy sounding, particularly in mono, but I think there’s something charming and quaint about the song’s cluttered vibe. Even when you listen to it now, it makes you feel like you’re hearing it on AM radio. It sounds like what a mid-60s pop song is supposed to sound like. I cherish that about it…

Lady Friend is not only the best thing David Crosby did with the Byrds but is the finest song of his career. It’s certainly one of my three or four favorite byrdsongs, though it can really be viewed as a David Crosby solo performance, Crosby having re-recorded his own harmony ovberdubs in place of McGuinn and Hillman’s initial backing vocals. McGuinn and Hillman are more or less reduced to being session players… As hard as it is to like Crosby the man, there’s no denying his massive talent as a vocalist, and he had some pretty good pop instincts as well, which are easily overlooked due to his much higher profile in Crosby Stills and Nash, where the whole point was to (d)evolve from the lightness of pop to the overwrought self-righteousness of corporate hippy rock. I don’t dislike CSN. They made a lot of good music and occupied a big place in my childhood. On a personal level, they make me think of the hours and hours I spent alone in my room as a kid. It’s not always a set of memories I want to return to, but they definitely made me feel less alone back then. It still blows my mind when I think of CSN as essentially the Byrds + Buffalo Springfield + the Hollies. The thing is, though, I’ll take any one of those three bands over CSN any day of the week. Even with CSN’s unmatched harmonies, they just sound too serious about themselves for my taste. I didn’t recognize this about them when I was little, or if I did I interpreted it as cool hippy earnestness, something to emulate. We get more jaded and cynical as we age and nowadays CSN strike me as a symbol of everything that went wrong in the late 60s. Even their vaunted harmonies sound shrill to me now, exquisitely executed and oh so heavy handed... Lady Friend was Crosby’s last stab at the pop life. He went about it using the Gene Clark Happy/Sad song formula and added a lovely orchestral sheen. I’m not sure who arranged the horns. I tend to be suspicious of horns and really anything that makes guitars harder to hear, but the horns in Lady Friend really elevate the song into the realm of great pop art. Crosby’s two other masterpieces from this period, Draft Morning and Triad, are really pop/rock hybrids. They’re terrific songs, but they lack Lady Friend’s pop purity. …Crosby was apparently unhappy with the way Gary Usher mixed Lady Friend. It’s admittedly a bit muddy sounding, particularly in mono, but I think there’s something charming and quaint about the song’s cluttered vibe. Even when you listen to it now, it makes you feel like you’re hearing it on AM radio. It sounds like what a mid-60s pop song is supposed to sound like. I cherish that about it…jingle jangle mornings, four

Q: What do the Byrds and Paul Revere and the Raiders have in common? Give up? A: Both were produced by Terry Melcher. There’s a tendency to not take the Raiders seriously. Dressing up in Revolutionary War garb will have this effect. I happen to think the duds are fun, and ‘kinda cool. More importantly, the Raiders had some great songs and there’s an unmistakable edge underneath all the dressup. I think this is Mr. Melcher’s influence. And it’s quite likely via Melcher that we can hear echoes of the Byrds in the marvelous 12-string jangle that’s at the heart of Kicks, written by the dynamic hubby ‘n wife duo of Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil...

Q: What do the Byrds and Paul Revere and the Raiders have in common? Give up? A: Both were produced by Terry Melcher. There’s a tendency to not take the Raiders seriously. Dressing up in Revolutionary War garb will have this effect. I happen to think the duds are fun, and ‘kinda cool. More importantly, the Raiders had some great songs and there’s an unmistakable edge underneath all the dressup. I think this is Mr. Melcher’s influence. And it’s quite likely via Melcher that we can hear echoes of the Byrds in the marvelous 12-string jangle that’s at the heart of Kicks, written by the dynamic hubby ‘n wife duo of Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil...

It’s easy enough to poo poo Kicks as the prototype for Just Say No, as a conservative PSA masquerading as social commentary, as folk rock for young Republicans, and on and on. I’m more charitable than this for no other reason than that the song fucking swings. Mark Lindsey’s delivery of its message is utterly inspired. The earnestness in his voice makes you drop your guard. And every junkie’s like a setting sun. The irony is that Melcher was in all likelihood stoned out of his mind during the recording sessions. But who cares if the message is jive and square - and who gives a shit if the band dresses up like George Washington - when you have a song that’s so economical in delivering pop perfection?

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

byrdsongs, xvi

Wanna have your mind blown in less than two minutes? Renaissance Fair is a delightfully heady piece of classically-infused pop, among the most ambitious songs the Byrds ever did. The music pulls you in right away. I think that maybe I’m dreaming. Me, too. I can’t tell if this is real, or a hallucinatory reverie, or somewhere between the two. “In between” is actually a good way to describe the music’s basic vibe. Things are in motion, in flux, interstitial, transforming, becoming different somehow. For a song that’s so light on its feet, the rhythm section is surprisingly heavy, but not in the bloozey sense of heaviness, more just insistent, or prominent, suggesting a point of no return, the breaching of a threshold. Make no mistake, this is pop of the highest caliber, undermined as such only a little by its conceptual aspirations, and all the more poignant for being a document of a sensibility in decline…

Wanna have your mind blown in less than two minutes? Renaissance Fair is a delightfully heady piece of classically-infused pop, among the most ambitious songs the Byrds ever did. The music pulls you in right away. I think that maybe I’m dreaming. Me, too. I can’t tell if this is real, or a hallucinatory reverie, or somewhere between the two. “In between” is actually a good way to describe the music’s basic vibe. Things are in motion, in flux, interstitial, transforming, becoming different somehow. For a song that’s so light on its feet, the rhythm section is surprisingly heavy, but not in the bloozey sense of heaviness, more just insistent, or prominent, suggesting a point of no return, the breaching of a threshold. Make no mistake, this is pop of the highest caliber, undermined as such only a little by its conceptual aspirations, and all the more poignant for being a document of a sensibility in decline…Tuesday, August 14, 2012

jingle jangle mornings, three

Today’s jingle jangle comes from an unlikely source. Cream is not a band that comes to mind when you’re thinking about jangly guitars and intricate little pop songs. They were a blooze-based sledge hammer of a power trio. Anybody who’s listened to Live Cream, or to Live Cream II, or to a good portion of Wheels of Fire knows that Cream were all about full-on flatulence, stretching things out to the breaking point, powered by a guitar god and what may be the heaviest rhythm section of all time. But there are actually a few touches of subtlety on Disraeli Gears, and it’s not just subtlety relative to Cream’s more typical M.O… I absolutely worshipped Cream when I was a kid. I loved the way Jack Bruce wailed the words, and the way his thunderous bass lines would shake the room like an earthquake…loved Ginger Baker’s insane drumming…and loved Clapton’s guitar, of course. I’ve probably heard Disraeli Gears all the way through 500 times, and I’d venture to guess that 90 percent of those listening sessions took place before I was 13 years old. I’ve since cultivated better taste, I think, I hope. But Dance the Night Away is a strange anomaly for Cream. The song is downright Beatles-ish if you can imagine Ginger sitting in for Ringo. The pounding of the tom toms and the heavy bass drum are the only trace of Cream as Cream. The rest of it jangles with ethereal lightness and grace…

Today’s jingle jangle comes from an unlikely source. Cream is not a band that comes to mind when you’re thinking about jangly guitars and intricate little pop songs. They were a blooze-based sledge hammer of a power trio. Anybody who’s listened to Live Cream, or to Live Cream II, or to a good portion of Wheels of Fire knows that Cream were all about full-on flatulence, stretching things out to the breaking point, powered by a guitar god and what may be the heaviest rhythm section of all time. But there are actually a few touches of subtlety on Disraeli Gears, and it’s not just subtlety relative to Cream’s more typical M.O… I absolutely worshipped Cream when I was a kid. I loved the way Jack Bruce wailed the words, and the way his thunderous bass lines would shake the room like an earthquake…loved Ginger Baker’s insane drumming…and loved Clapton’s guitar, of course. I’ve probably heard Disraeli Gears all the way through 500 times, and I’d venture to guess that 90 percent of those listening sessions took place before I was 13 years old. I’ve since cultivated better taste, I think, I hope. But Dance the Night Away is a strange anomaly for Cream. The song is downright Beatles-ish if you can imagine Ginger sitting in for Ringo. The pounding of the tom toms and the heavy bass drum are the only trace of Cream as Cream. The rest of it jangles with ethereal lightness and grace…