It’s amazing what ten years off the grid did for Roger McGuinn creatively. Back From Rio is by no means a perfect record, but it’s easily the best thing he’d done since the Byrds’ Untitled, 20 years or so earlier. I’m not sure what accounts for this rebirth of sorts. Maybe he just needed the rest. Or maybe the imminent induction of the Byrds into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame put him in touch with the brilliance of his band’s classic period. Or maybe once punk and post-punk finally destroyed the dominance of the FM Corporate Rock Behemoth, McGuinn drew inspiration from all the Byrds-influenced music that appeared on the scene. Whatever the reason, Back From Rio is a welcome return to form. Tonight’s song, a duet with Tom Petty, is the single from the album, supposedly written when McGuinn joined the Heartbreakers while they were the backing band for Bob Dylan on on the True Confessions tour in the mid 80s. Sadly, I was too much of a punk/post-punk snob at the time to see this tour. But the idea of McGuinn and Mike Campbell playing together on the same stage makes me salivate. Campbell gets a playing credit on Back From Rio, though I’m not sure which tracks he plays on. I’d guess he’s definitely playing on King of the Hill, an orgy of luscious guitars layered on top of one another. I think the song would be even better if McGuinn sang the whole thing instead of giving a verse to Petty, but this is just quibbling. Their braying voices are quite similar and, in any case, the singing is beside the point. This one is undoubtedly all about those beautiful guitars. Welcome back from Rio, Mr. McGuinn!

It’s amazing what ten years off the grid did for Roger McGuinn creatively. Back From Rio is by no means a perfect record, but it’s easily the best thing he’d done since the Byrds’ Untitled, 20 years or so earlier. I’m not sure what accounts for this rebirth of sorts. Maybe he just needed the rest. Or maybe the imminent induction of the Byrds into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame put him in touch with the brilliance of his band’s classic period. Or maybe once punk and post-punk finally destroyed the dominance of the FM Corporate Rock Behemoth, McGuinn drew inspiration from all the Byrds-influenced music that appeared on the scene. Whatever the reason, Back From Rio is a welcome return to form. Tonight’s song, a duet with Tom Petty, is the single from the album, supposedly written when McGuinn joined the Heartbreakers while they were the backing band for Bob Dylan on on the True Confessions tour in the mid 80s. Sadly, I was too much of a punk/post-punk snob at the time to see this tour. But the idea of McGuinn and Mike Campbell playing together on the same stage makes me salivate. Campbell gets a playing credit on Back From Rio, though I’m not sure which tracks he plays on. I’d guess he’s definitely playing on King of the Hill, an orgy of luscious guitars layered on top of one another. I think the song would be even better if McGuinn sang the whole thing instead of giving a verse to Petty, but this is just quibbling. Their braying voices are quite similar and, in any case, the singing is beside the point. This one is undoubtedly all about those beautiful guitars. Welcome back from Rio, Mr. McGuinn!Wednesday, October 31, 2012

byrdsongs, lxxx

It’s amazing what ten years off the grid did for Roger McGuinn creatively. Back From Rio is by no means a perfect record, but it’s easily the best thing he’d done since the Byrds’ Untitled, 20 years or so earlier. I’m not sure what accounts for this rebirth of sorts. Maybe he just needed the rest. Or maybe the imminent induction of the Byrds into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame put him in touch with the brilliance of his band’s classic period. Or maybe once punk and post-punk finally destroyed the dominance of the FM Corporate Rock Behemoth, McGuinn drew inspiration from all the Byrds-influenced music that appeared on the scene. Whatever the reason, Back From Rio is a welcome return to form. Tonight’s song, a duet with Tom Petty, is the single from the album, supposedly written when McGuinn joined the Heartbreakers while they were the backing band for Bob Dylan on on the True Confessions tour in the mid 80s. Sadly, I was too much of a punk/post-punk snob at the time to see this tour. But the idea of McGuinn and Mike Campbell playing together on the same stage makes me salivate. Campbell gets a playing credit on Back From Rio, though I’m not sure which tracks he plays on. I’d guess he’s definitely playing on King of the Hill, an orgy of luscious guitars layered on top of one another. I think the song would be even better if McGuinn sang the whole thing instead of giving a verse to Petty, but this is just quibbling. Their braying voices are quite similar and, in any case, the singing is beside the point. This one is undoubtedly all about those beautiful guitars. Welcome back from Rio, Mr. McGuinn!

It’s amazing what ten years off the grid did for Roger McGuinn creatively. Back From Rio is by no means a perfect record, but it’s easily the best thing he’d done since the Byrds’ Untitled, 20 years or so earlier. I’m not sure what accounts for this rebirth of sorts. Maybe he just needed the rest. Or maybe the imminent induction of the Byrds into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame put him in touch with the brilliance of his band’s classic period. Or maybe once punk and post-punk finally destroyed the dominance of the FM Corporate Rock Behemoth, McGuinn drew inspiration from all the Byrds-influenced music that appeared on the scene. Whatever the reason, Back From Rio is a welcome return to form. Tonight’s song, a duet with Tom Petty, is the single from the album, supposedly written when McGuinn joined the Heartbreakers while they were the backing band for Bob Dylan on on the True Confessions tour in the mid 80s. Sadly, I was too much of a punk/post-punk snob at the time to see this tour. But the idea of McGuinn and Mike Campbell playing together on the same stage makes me salivate. Campbell gets a playing credit on Back From Rio, though I’m not sure which tracks he plays on. I’d guess he’s definitely playing on King of the Hill, an orgy of luscious guitars layered on top of one another. I think the song would be even better if McGuinn sang the whole thing instead of giving a verse to Petty, but this is just quibbling. Their braying voices are quite similar and, in any case, the singing is beside the point. This one is undoubtedly all about those beautiful guitars. Welcome back from Rio, Mr. McGuinn!Monday, October 29, 2012

byrdsongs, lxxvix

Roger McGuinn’s Back From Rio came out while I was living in the UK. I got to hear him play at the Cambridge Corn Exchange, one of the best concerts I’ve ever been to. And while I think the pop life seeds were in my circuitry from the very beginning of my life - an aural aesthetic fusing beauty, tragedy and romance into something so alluring that it becomes a kind of worldview - I don’t think that any of this became fully explicit for me until that night at the Corn Exchange. I heard McGuinn’s 12-string Rickenbacker ringing out sublimely into the night, and in that moment I knew what I was about. I can’t even really fully articulate what I felt, but I know it included joy, a sense of belonging, a feeling of inclusion... I knew then that Roger McGuinn gets me, and if he gets me there must be others who get me, too. I know all of this probably seems vague and not entirely coherent, but it’s just so hard to get at what I’m trying to explain. I think tonight’s song does a better job than I could do with a million words. Listen to the jangle of the dual 12-string guitars and perhaps you’ll understand. Listen to the lush harmonies, and to the song’s addictive tunefulness. You might notice a feeling of dread building inside you as the song fades, as if you’re about to be abandoned by a loved one, but then you’ll quickly come to the realization that, unlike the loved one who’s gone to stay, you can experience the beauty of this song again, and again…

Roger McGuinn’s Back From Rio came out while I was living in the UK. I got to hear him play at the Cambridge Corn Exchange, one of the best concerts I’ve ever been to. And while I think the pop life seeds were in my circuitry from the very beginning of my life - an aural aesthetic fusing beauty, tragedy and romance into something so alluring that it becomes a kind of worldview - I don’t think that any of this became fully explicit for me until that night at the Corn Exchange. I heard McGuinn’s 12-string Rickenbacker ringing out sublimely into the night, and in that moment I knew what I was about. I can’t even really fully articulate what I felt, but I know it included joy, a sense of belonging, a feeling of inclusion... I knew then that Roger McGuinn gets me, and if he gets me there must be others who get me, too. I know all of this probably seems vague and not entirely coherent, but it’s just so hard to get at what I’m trying to explain. I think tonight’s song does a better job than I could do with a million words. Listen to the jangle of the dual 12-string guitars and perhaps you’ll understand. Listen to the lush harmonies, and to the song’s addictive tunefulness. You might notice a feeling of dread building inside you as the song fades, as if you’re about to be abandoned by a loved one, but then you’ll quickly come to the realization that, unlike the loved one who’s gone to stay, you can experience the beauty of this song again, and again… Sunday, October 28, 2012

byrdsongs, lxxviii

Chris Hillman had a great deal of success with the Desert Rose Band. But you wouldn't know this unless you listen to FM country stations, which I never do because most of that music sounds to me like the soundtrack to a lynching. I realize that probably sounds snobby and narrow-minded, but it's how I feel. It's a symptom of how polarized America has become. I don't even wanna dabble in anything that's associated with the red states, except maybe good barbecue. I hope - but have no real way of finding out - that Hillman is an anomaly in that world, that he's not of the same ilk as so many of the backwoods folks who I imagine are the DRB's hardcore constituents. The reason I mention all this is that, if you're like me, you probably had no idea (until I told you) that the DRB had a Number One hit on the country charts with today's song in 1988. And guess what? In spite of everything I've said here, it's a lovely song. I stepped outside my bubble for a few minutes and was actually rewarded for it. Perhaps there's a lesson here...

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Earle Mankey Appreciation Society, 2

I didn't have any awareness of Earle Mankey when I was a teenager, but I ran out and bought the one and only Tress album, Sleep Convention, which Mankey produced, immediately after seeing the video for Delta Sleep on MTV, circa 1983. It is one of the most hauntingly gorgeous tunes you'll ever hear. The great thing about New Wave is the emphasis on minimalism, the idea being that there's a paradox in music where the more spare it is, the more dramatic it sounds. I don't think this is always and everywhere the case, but there's something to be said for leaving some things to the imagination, allowing thoughts to run wild in an uncluttered soundscape. This is exactly what happens with Trees. I wouldn't say their music is simple because you'll hear some fairly unusual chord changes in the songs, and some freaky play with tempo, so perhaps frugal is a better word, frugal yet extremely heady and deep. Delta Sleep was perfect for me at the time. And like so much of the music Mankey's been involved in, it's the kind of song that sticks around in your head for a long time. Mankey's work for Sleep Convention necessarily sounds a bit dated now, but he coaxed some amazing music out of Trees. Time hasn't diminished the power of the songs on Sleep Convention one bit...

Friday, October 26, 2012

byrdsongs, lxxvii

I’ve always had the impression that country music is Chris Hillman’s first love. Rock ‘n roll was just something he did because he’s an accomplished and versatile musician, and he was in the right place at the right time in the 60s, but country and blue grass are the core components of his musical identity. Many weeks ago now, I pointed out that Hillman more or less invented country rock, for better or worse, as early as 1966, with his country flavored pop tunes on Younger than Yesterday. To any keen observer of the Byrds and their aftermaths, Hillman’s direction in the latter half of the 80s and early 90s comes as no surprise, a full-fledged embrace of purist c&w, first on his solo record, Desert Rose, and then in four records released with the Desert Rose Band. This stuff is country music, pure and simple, the kind of thing you hear on FM c&w stations, though it thankfully steers clear of the I love the USA yahoo shit. The DRB is even less palatable to me than Gram Parsons’ solo material, which doesn’t mean it’s bad music, just that I don’t particularly go for this sort of thing. Objectively speaking, if that’s even possible in music, I’ll tell you that the DRB are very good at what they do. And it’s hard to argue with their success in the c&w charts. In 1987, tonight’s song went as high as Number 2, with a bullet, on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles and Tracks. The return to his deepest musical passions gave Hillman a new lease on life. I don’t have to like the DRB’s music to be happy for the man whose rumbling bass line turned Eight Miles High into such a psychedelic beast, and who was so instrumental in the making of The Notorious Byrd Brothers. I'm glad to see that sometimes success is simply a matter of following your bliss…

I’ve always had the impression that country music is Chris Hillman’s first love. Rock ‘n roll was just something he did because he’s an accomplished and versatile musician, and he was in the right place at the right time in the 60s, but country and blue grass are the core components of his musical identity. Many weeks ago now, I pointed out that Hillman more or less invented country rock, for better or worse, as early as 1966, with his country flavored pop tunes on Younger than Yesterday. To any keen observer of the Byrds and their aftermaths, Hillman’s direction in the latter half of the 80s and early 90s comes as no surprise, a full-fledged embrace of purist c&w, first on his solo record, Desert Rose, and then in four records released with the Desert Rose Band. This stuff is country music, pure and simple, the kind of thing you hear on FM c&w stations, though it thankfully steers clear of the I love the USA yahoo shit. The DRB is even less palatable to me than Gram Parsons’ solo material, which doesn’t mean it’s bad music, just that I don’t particularly go for this sort of thing. Objectively speaking, if that’s even possible in music, I’ll tell you that the DRB are very good at what they do. And it’s hard to argue with their success in the c&w charts. In 1987, tonight’s song went as high as Number 2, with a bullet, on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles and Tracks. The return to his deepest musical passions gave Hillman a new lease on life. I don’t have to like the DRB’s music to be happy for the man whose rumbling bass line turned Eight Miles High into such a psychedelic beast, and who was so instrumental in the making of The Notorious Byrd Brothers. I'm glad to see that sometimes success is simply a matter of following your bliss…Thursday, October 25, 2012

byrdsongs, lxxvi

So dig this. There’s always more to learn. You never know it all. I wanted to write about Gene Clark’s cameo appearance on the Long Ryders’ Native Sons, singing backing vox on Ivory Tower, but the only versions of the song available on Youtube are recent live performances, sans Clark, of course. So I turned my attention to Clark’s involvement (musical only, as far as I know) with Carla Olson. The duo recorded So Rebellious A Lover, Clark’s last record. Olson is best known as being the face of the Textones, an 80s alterna-rootsy-country-folky-college radio-ish kinda thing. The rest of the Textones all play on So Rebellious, so it’s really a Textones record with Gene Clark added to the mix. Full confession: I’d never heard the record until a few days ago because, notwithstanding his appearance on the Long Ryders album, the idea of Clark being thrown a bone by an 80s roots/revivalist band depresses me on several levels...

So dig this. There’s always more to learn. You never know it all. I wanted to write about Gene Clark’s cameo appearance on the Long Ryders’ Native Sons, singing backing vox on Ivory Tower, but the only versions of the song available on Youtube are recent live performances, sans Clark, of course. So I turned my attention to Clark’s involvement (musical only, as far as I know) with Carla Olson. The duo recorded So Rebellious A Lover, Clark’s last record. Olson is best known as being the face of the Textones, an 80s alterna-rootsy-country-folky-college radio-ish kinda thing. The rest of the Textones all play on So Rebellious, so it’s really a Textones record with Gene Clark added to the mix. Full confession: I’d never heard the record until a few days ago because, notwithstanding his appearance on the Long Ryders album, the idea of Clark being thrown a bone by an 80s roots/revivalist band depresses me on several levels...  But a little bell rang in the back of my brain, a barely remembered connection. Then it hit me: Didn’t Phil Seymour play in the Textones after his attempt at a solo career went south? Google says yes! Worlds collide when you live the pop life! ...It would appear, then, that the Textones are the band where my faded pop life idols go before they die. Seymour passed on a few years after Clark. Both of them play on So Rebellious. And much to my pleasant surprise, it’s a pretty nice collection of tunes. Tonight’s song is quite haunting when you put it in context. It's probably not something you need to hear every day, but it makes me feel good to know that Clark went out on a good note. I can’t really tell whether it's Phil Seymour behind the drum kit in the footage, but I’d like to think it is. The thought of those two shooting stars on stage together brings a smile to my face...

But a little bell rang in the back of my brain, a barely remembered connection. Then it hit me: Didn’t Phil Seymour play in the Textones after his attempt at a solo career went south? Google says yes! Worlds collide when you live the pop life! ...It would appear, then, that the Textones are the band where my faded pop life idols go before they die. Seymour passed on a few years after Clark. Both of them play on So Rebellious. And much to my pleasant surprise, it’s a pretty nice collection of tunes. Tonight’s song is quite haunting when you put it in context. It's probably not something you need to hear every day, but it makes me feel good to know that Clark went out on a good note. I can’t really tell whether it's Phil Seymour behind the drum kit in the footage, but I’d like to think it is. The thought of those two shooting stars on stage together brings a smile to my face...Tuesday, October 23, 2012

byrdsongs, lxxv

Boy, the layers of tin foil you have to peel away in order to get to tonight’s song are really quite obtrusive. There’s a very good tune underneath it all but the mix is completely swampy and claustrophobic. Sometimes it seems like 80s production was designed to make it almost impossible to hear music as anything more than muddled mush. But I give Gene Clark credit. He recorded Firebyrd after spending some time with Jesse Ed Davis in Hawaii trying to rehab off drugs. That he was able to be productive at all at this point is pretty remarkable. Rain Song is the best tune on Firebyrd, the appearance of which loosely coincided with the brief revivalist excitement of the Paisley Underground in Los Angeles. Clark became hip again for awhile as not only the Paisley Underground bands, but also REM, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Tommy Keene, and the dbs, to name just a few, referenced the Byrds with a new explicitness. Unfortunately, Clark was not able to parlay his newfound cache into something more enduring and he eventually slid back into drugs, drink and inner torment. The guy had so much talent but couldn’t get past his demons. It’s very sad, but he continued to make music through these struggles and its from this that we can draw a small measure of inspiration...

Boy, the layers of tin foil you have to peel away in order to get to tonight’s song are really quite obtrusive. There’s a very good tune underneath it all but the mix is completely swampy and claustrophobic. Sometimes it seems like 80s production was designed to make it almost impossible to hear music as anything more than muddled mush. But I give Gene Clark credit. He recorded Firebyrd after spending some time with Jesse Ed Davis in Hawaii trying to rehab off drugs. That he was able to be productive at all at this point is pretty remarkable. Rain Song is the best tune on Firebyrd, the appearance of which loosely coincided with the brief revivalist excitement of the Paisley Underground in Los Angeles. Clark became hip again for awhile as not only the Paisley Underground bands, but also REM, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Tommy Keene, and the dbs, to name just a few, referenced the Byrds with a new explicitness. Unfortunately, Clark was not able to parlay his newfound cache into something more enduring and he eventually slid back into drugs, drink and inner torment. The guy had so much talent but couldn’t get past his demons. It’s very sad, but he continued to make music through these struggles and its from this that we can draw a small measure of inspiration...Monday, October 22, 2012

byrdsongs, lxxiv

The hippie cum yuppie – or yuppified hippie – is an important demographic to keep in mind in considering the music of the 80s. Much of what I used to view on MTV (while waiting hours upon hours for something masturbatable to be shown) were videos by 60s and 70s stars trying to make the transition to the 80s. Tina Turner. Jackson Browne (hardly a ‘holdout’). Henley/Frey. Elton John. Genesis/Peter Gabriel/Phil Collins. Queen. Springsteen. Bowie… You get the picture. Execrable stuff, for the most part. Give the song a tinny arrangement, replete with the requisite drum box, and give the singer a mullet and/or a pastel colored leather jacket, and there they are, right at home in the era of Ivan Boesky and Iran-Contra. Can I get another bottle of sake with my California roll?

The hippie cum yuppie – or yuppified hippie – is an important demographic to keep in mind in considering the music of the 80s. Much of what I used to view on MTV (while waiting hours upon hours for something masturbatable to be shown) were videos by 60s and 70s stars trying to make the transition to the 80s. Tina Turner. Jackson Browne (hardly a ‘holdout’). Henley/Frey. Elton John. Genesis/Peter Gabriel/Phil Collins. Queen. Springsteen. Bowie… You get the picture. Execrable stuff, for the most part. Give the song a tinny arrangement, replete with the requisite drum box, and give the singer a mullet and/or a pastel colored leather jacket, and there they are, right at home in the era of Ivan Boesky and Iran-Contra. Can I get another bottle of sake with my California roll?  Once in awhile, though, this bridge connecting the 60s to the 80s produced some good stuff. I’m not talking about revivalism here, which is a different animal altogether. I’m thinking instead of songs that sound 80sish and gain emotional resonance from the dashed dreams/ideals of the grizzled artists who perform them. I’ve written about this before. My favorite example is Don Henley’s Boys of Summer, the original version of which has been scrubbed from Youtube because, after all, yuppie sensitivity is the former as much as it is the latter. But I happen to think it’s one of the best pop songs ever recorded, and certainly the greatest to come out of the 80s. The production is absolutely awful, awash in mechanized drums and synthesizers, but this only bolsters the music’s tragic ethos, giving the song a feeling of loss as it conjures up images of a one-time long hair, now neatly groomed and adrift in a sea of consumerism, with credit card in hand, but no longer in possession the moral high ground. The famous line about the deadhead sticker on a Cadillac makes a lot of people wince, especially coming from someone as shysterish as Don Henley. But I love it, and no amount of computerized effects can diminish the chills I get as the guitar fades the song out. It makes me feel like I'm wandering the aisles at Pottery Barn, in a good way. I really wish I could post the video for you because it’s of that era where the song feels somewhat incomplete without its video.

Once in awhile, though, this bridge connecting the 60s to the 80s produced some good stuff. I’m not talking about revivalism here, which is a different animal altogether. I’m thinking instead of songs that sound 80sish and gain emotional resonance from the dashed dreams/ideals of the grizzled artists who perform them. I’ve written about this before. My favorite example is Don Henley’s Boys of Summer, the original version of which has been scrubbed from Youtube because, after all, yuppie sensitivity is the former as much as it is the latter. But I happen to think it’s one of the best pop songs ever recorded, and certainly the greatest to come out of the 80s. The production is absolutely awful, awash in mechanized drums and synthesizers, but this only bolsters the music’s tragic ethos, giving the song a feeling of loss as it conjures up images of a one-time long hair, now neatly groomed and adrift in a sea of consumerism, with credit card in hand, but no longer in possession the moral high ground. The famous line about the deadhead sticker on a Cadillac makes a lot of people wince, especially coming from someone as shysterish as Don Henley. But I love it, and no amount of computerized effects can diminish the chills I get as the guitar fades the song out. It makes me feel like I'm wandering the aisles at Pottery Barn, in a good way. I really wish I could post the video for you because it’s of that era where the song feels somewhat incomplete without its video. …Another example of a song with the same impact, maybe a little less stark because the vibe is so much sunnier, is CSN’s Southern Cross. I defy you to tell me this tune doesn't swing, doesn't have a melody that rings in your brain all day long, doesn't make you wanna hear it again and again, doesn't leave you with the (albeit fleeting) feeling that maybe the hippies are ok after all. And just listen to those harmonies! I think this just might be my favorite CSN song. I shit you not. It's from 1982 for god's sake, a song you might hear blasting out the windows of a DeLorean while waiting for the light to turn green on the exit ramp at Coldwater Canyon. You Know love can endure, and you know it will. I can't really relate to this particular sentiment, but one doesn’t have to because the song’s power derives from its sense of yearning for so much more than its era can provide…

…Another example of a song with the same impact, maybe a little less stark because the vibe is so much sunnier, is CSN’s Southern Cross. I defy you to tell me this tune doesn't swing, doesn't have a melody that rings in your brain all day long, doesn't make you wanna hear it again and again, doesn't leave you with the (albeit fleeting) feeling that maybe the hippies are ok after all. And just listen to those harmonies! I think this just might be my favorite CSN song. I shit you not. It's from 1982 for god's sake, a song you might hear blasting out the windows of a DeLorean while waiting for the light to turn green on the exit ramp at Coldwater Canyon. You Know love can endure, and you know it will. I can't really relate to this particular sentiment, but one doesn’t have to because the song’s power derives from its sense of yearning for so much more than its era can provide…Sunday, October 21, 2012

Earle Mankey Appreciation Society, 1

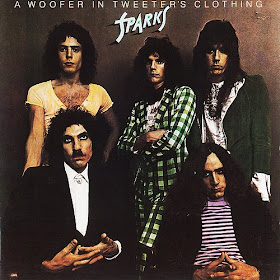

One of PLU's iron-clad axions when it comes to pop music is that if Earle Mankey is involved, it's gonna be good. A few days ago, I was thinking about the music I listened to in high school, and I remembered a record I bought when I was in 9th grade, Sleep Convention, by a band called Trees. I'll post a song or two from the album in the next few days, but for now suffice it to say that the album had a profound impact on me. Trees were definitely New Wave. The songs on Sleep Convention are arty but also amazingly tuneful. Artiness often prevents music from being tuneful because a big part of artiness is dissonance, and usually dissonance is the opposite of tunefulness. Arty tunefulness is extremely rare. Bowie made a career of it, but Bowie is Bowie, and let's just say that not a lot of people can do what he does, no matter how talented they are. So, anyway, I was thinking about how much I loved Trees. I started poking around on the internet for info about Sleep Convention, and I found out that it was produced by Earl Mankey. I didn't know this back then. I didn't even know who Mankey was until I moved to LA. Let's call this the Earle Mankey Effect: You hear something that's somewhat obscure, but it's also incredibly hooky and has a cool L.A. vibe, and you eventually discover that it's produced by Earle Mankey. This has happened to me on at least a half-dozen occasions. Back in the early 70s, Mankey was the guitarist on the first two Sparks records. Sparks are an acquired taste. It can be a bit of a challenge to get past their campiness, but the hooks eventually sink in if you're patient. And once they do sink in, the music becomes a bit of an addiction. Something tells me this addictiveness is, in large part, Earle Mankey's doing...

Saturday, October 20, 2012

byrdsongs, lxxiii

City is the last album Roger McGuinn was involved in before more or less falling off the grid in the 80s. I don't have a lot of familiarity with it because, in my life as a Byrds fanatic over the past 20-some-odd years, it's always appeared to me as a record that's probably best avoided. The sleeve makes it seem like one of those horrible 60s-guys- trying-to-do-80s-music monstrosities. My copy of the record (when I still owned records) was pressed on thin, cheap, mass-produced vinyl, the kind of thing that puts me in touch with the sense of dread people like me (liberal, neurotic, pessimistic) must have had as the Reagan era beckoned. Also, the record is credited to Roger McGuinn and Chris Hiilman "featuring Gene Clark," which, knowing what I know, is hard for me not to interpret as 'Gene's too fucked up to be a full-on participant on this one.' And that depresses me. You know what, though? That cliched thing about not judging a book by its cover turns out to be some serious wisdom in this case. I wouldn't say City is a great record. I'd even be hard pressed to say it's a good record. But it was easily the best thing these guys had done in god knows how long. This is probably a minority opinion, mind you. There doesn't seem to be much written about the record anywhere. This is likely because the music suffers from much of what the sleeve telegraphs that it's going to suffer from (so maybe the point is that judging a book by its cover is ok, as long as you keep a semi-open mind). The overall sound on City is, as expected, flat and tinny, in keeping with what all records sounded like starting in the late 70s. But some of the material is pretty ok, even when the guys try to be "current" with New Wavey sounding arrangements or songs about rollerskating. Your initial response might be to laugh with derision, but give at least some of these songs a chance. I hear McGuinn's 12-string chiming away here and there, albeit under layers and layers of 80s tin foil, and I think to myself, 'this works, sort of...'

Thursday, October 18, 2012

byrdsongs, lxxii

You’d think that with McGuinn, Clark and Hillman getting together again, this time without having to contend with Crosby’s ego and general douchebaggery, they could have created something so much better. You’d think they’d have learned a thing or two from the horrible Byrds reunion album they’d done a few years earlier. You’d think that by 1979 they’d have had their ear to the ground a bit more, noticed the workability of revivalism, and gotten back to what made them so great in the beginning. On the other hand, maybe these implicit criticisms are unfair. Maybe they didn’t want to go back to making Byrdsy music because doing so would have felt like taking steps backwards. I don’t know the reasons why the reunion this time around replicated the bland corporate rock stylings of the previous reunion. I really don't. Ask yourself this question: If McGuinn Clark and Hillman weren’t McGuinn, Clark and Hillman but released the same music that’s on the McGuinn Clark and Hillman album, would anybody have given them the time of day? ...When you watch tonight’s clip, in which MC&H perform the only good song on their self-titled album, you'll notice that Clark is completely out of it. He's there but he’s not there. Is his mic even turned on? Is his guitar plugged in? What near-lethal concoction do you think is coursing through his body as he's 'performing'? And elsewhere on the stage, who’s the dude with the black Stratocaster, wearing that horrible puke-colored shirt with the white tassels? He's like an archetype of the tacky 70s LA session player. On the plus side, Roger’s using a capo on his 12-string. I wonder if this is because it’s one of those old-style acoustic twelves where the truss rod isn’t strong enough to keep the guitar in standard tuning, or whether he just wanted to take things a few steps higher. I know you don’t care, and I’m sorry. I’m just vamping, looking for something interesting to point out. It hasn’t been easy these past few weeks. As far as I’m concerned, the 70s couldn’t end soon enough when it came to those guys who'd once called themselves the Byrds…

You’d think that with McGuinn, Clark and Hillman getting together again, this time without having to contend with Crosby’s ego and general douchebaggery, they could have created something so much better. You’d think they’d have learned a thing or two from the horrible Byrds reunion album they’d done a few years earlier. You’d think that by 1979 they’d have had their ear to the ground a bit more, noticed the workability of revivalism, and gotten back to what made them so great in the beginning. On the other hand, maybe these implicit criticisms are unfair. Maybe they didn’t want to go back to making Byrdsy music because doing so would have felt like taking steps backwards. I don’t know the reasons why the reunion this time around replicated the bland corporate rock stylings of the previous reunion. I really don't. Ask yourself this question: If McGuinn Clark and Hillman weren’t McGuinn, Clark and Hillman but released the same music that’s on the McGuinn Clark and Hillman album, would anybody have given them the time of day? ...When you watch tonight’s clip, in which MC&H perform the only good song on their self-titled album, you'll notice that Clark is completely out of it. He's there but he’s not there. Is his mic even turned on? Is his guitar plugged in? What near-lethal concoction do you think is coursing through his body as he's 'performing'? And elsewhere on the stage, who’s the dude with the black Stratocaster, wearing that horrible puke-colored shirt with the white tassels? He's like an archetype of the tacky 70s LA session player. On the plus side, Roger’s using a capo on his 12-string. I wonder if this is because it’s one of those old-style acoustic twelves where the truss rod isn’t strong enough to keep the guitar in standard tuning, or whether he just wanted to take things a few steps higher. I know you don’t care, and I’m sorry. I’m just vamping, looking for something interesting to point out. It hasn’t been easy these past few weeks. As far as I’m concerned, the 70s couldn’t end soon enough when it came to those guys who'd once called themselves the Byrds…Wednesday, October 17, 2012

byrdsongs, lxxi

It is, of course, quite difficult to make a convincing case for CSN in the context of punk and New Wave, and yet their eponymous 1977 album forces the issue with some surprisingly nice results. Perhaps this is merely the soft bigotry of low expectations talking. The record has a definite cocaine-corporate vibe that will remind you of it’s place, ten years removed from the Summer of Love. Whether these ten years were an eternity or the wink of an eye depends on your perspective, I suppose, but one hears the music on this record and pictures LA session players with permed hair, tight trousers, and shiny shirts opened to the fourth button, enough to reveal gold-plated chains burried amidst fulsome thatches of chest hair. Welcome to the 1970s, in other words. I’m too young to have experienced the 60s firsthand. but not too young to have been profoundly shaped by the long 60s hangover. When I was a kid, radio gave me a gateway out of sadness and confusion. I listened to WPLJ FM, and WNEW FM, and WABC AM in New York City. It’s interesting that the FM stations at this time tried to simultaneously assimilate punk and keep the 60s dream alive. This was before anyone used the term Classic Rock. It was all just rock, so you’d hear Elvis Costello, Marshall Crenshaw, Bruce Springsteen, the Rolling Stones, the Police, and CSN all in the same ‘block’ of songs. Just a Song Before I Go was played in these types of blocks all the time when I was 9 or 10 years old. There’s something about the song that enchanted me. When you’re that age, the lack of any sweeping perspective means there’s no possibility for ironic distancing, no cynicism, no jadedness, none of those things that eventually come to poison one’s frame of mind. Music in particular takes on a magical quality. Everything’s new and dazzling and fresh, especially if you’re wired for music at an especially sensitive psycho-physiological level. Just a Song Before I go hit me at just the right time to send my childlike imagination soaring. I realize now that the song is basically corporate M.O.R., but it retains an emotional resonance for me. Part of this is simply the emotional residue left over from my nine-year-old self. It never completely goes away. But I think there may be more going on here. One of the song’s strengths is that it’s so short. If only corporate rock could have kept things this compact and concise with more regularity! The shortness of the song elevates its tragic vibe. The music arrives with its soothing smoothness and lovely harmonies, and then it’s gone just as quickly, much like the song's protagonist, who's packing bags, navigating the dreariness of an airport, and taking leave of a loved one, possibly for good. I still remember how the song used to touch my soul and fill me with longing. Traveling twice the speed of sound, it’s easy to get burned. What a devastating line to hear when you’re 9…when you’re 39…when you’re 69. The music transcends its time and place. It’s a love song, to be sure, but it’s also a more general ode to something departed, something that was special yet taken for granted when it was still with you, and only now that it’s gone forever do you appreciate how much it should have been cherished, nurtured, and adored...

It is, of course, quite difficult to make a convincing case for CSN in the context of punk and New Wave, and yet their eponymous 1977 album forces the issue with some surprisingly nice results. Perhaps this is merely the soft bigotry of low expectations talking. The record has a definite cocaine-corporate vibe that will remind you of it’s place, ten years removed from the Summer of Love. Whether these ten years were an eternity or the wink of an eye depends on your perspective, I suppose, but one hears the music on this record and pictures LA session players with permed hair, tight trousers, and shiny shirts opened to the fourth button, enough to reveal gold-plated chains burried amidst fulsome thatches of chest hair. Welcome to the 1970s, in other words. I’m too young to have experienced the 60s firsthand. but not too young to have been profoundly shaped by the long 60s hangover. When I was a kid, radio gave me a gateway out of sadness and confusion. I listened to WPLJ FM, and WNEW FM, and WABC AM in New York City. It’s interesting that the FM stations at this time tried to simultaneously assimilate punk and keep the 60s dream alive. This was before anyone used the term Classic Rock. It was all just rock, so you’d hear Elvis Costello, Marshall Crenshaw, Bruce Springsteen, the Rolling Stones, the Police, and CSN all in the same ‘block’ of songs. Just a Song Before I Go was played in these types of blocks all the time when I was 9 or 10 years old. There’s something about the song that enchanted me. When you’re that age, the lack of any sweeping perspective means there’s no possibility for ironic distancing, no cynicism, no jadedness, none of those things that eventually come to poison one’s frame of mind. Music in particular takes on a magical quality. Everything’s new and dazzling and fresh, especially if you’re wired for music at an especially sensitive psycho-physiological level. Just a Song Before I go hit me at just the right time to send my childlike imagination soaring. I realize now that the song is basically corporate M.O.R., but it retains an emotional resonance for me. Part of this is simply the emotional residue left over from my nine-year-old self. It never completely goes away. But I think there may be more going on here. One of the song’s strengths is that it’s so short. If only corporate rock could have kept things this compact and concise with more regularity! The shortness of the song elevates its tragic vibe. The music arrives with its soothing smoothness and lovely harmonies, and then it’s gone just as quickly, much like the song's protagonist, who's packing bags, navigating the dreariness of an airport, and taking leave of a loved one, possibly for good. I still remember how the song used to touch my soul and fill me with longing. Traveling twice the speed of sound, it’s easy to get burned. What a devastating line to hear when you’re 9…when you’re 39…when you’re 69. The music transcends its time and place. It’s a love song, to be sure, but it’s also a more general ode to something departed, something that was special yet taken for granted when it was still with you, and only now that it’s gone forever do you appreciate how much it should have been cherished, nurtured, and adored...Monday, October 15, 2012

byrdsongs, lxx

in which Roger McGuinn lends further proof to Pop Life Unlimited’s Iron Law of Cover Versions, namely that they almost always suck. But this one really sucks. It’s hard for me to get my mind around the fact that this is the same guy who did this, and this, and this, and this. What a depressing difference a decade makes. You can tell that corporate rock is at its nadir when disco motifs begin to creep into the arrangements, not because disco is bad, but rather because hearing white rock guys from the 60s try to play disco will make you want to stick a sharp pencil in your eardrum. And when, at the beginning of tonight's clip, you see McGuinn swinging his tush to that disco beat, you may also be overcome with the desire to scratch your own eyes out...The original version of American Girl is not a perfect song. It’s almost ruined by the thumping bass line in the bridge (white disco rearing its ugly head here as well). But the song has elements of perfection. The main riff, played in octaves, is a thing of simple beauty. And then there's those lovely hand claps. The song’s spirit cries out for a joyride down Mulholland with the top down on your Mustang convertible, your best gal riding shotgun. Petty injects the music with a transcendent vibe, call it teen-o-rama (and all that melodrama), and Phil Seymour adds just the right touch with his cheeky little ‘make it last all night.’ So in some ways there’s no place to go but down if you try to cover the thing. And McGuinn covering a guy who many saw as himself a McGuinn copycat tells you everything you need to know about how lost Roger was by 1977. Thankfully, Thunderbyrd (oy vey) was the last solo album he put out for 13 years, and when he finally returned with Back From Rio, he'd regained his focus and got back to doing the kind of thing he was always meant to do. The break definitely did him some good, though there’s still the small matter of McGuinn Clark and Hillman…

Saturday, October 13, 2012

byrdsongs, lxvix

About three years passed between No Other and Two Sides to Every Story, released in January 1977. I'm getting a little tired of saying this, but it's not a very good record. Like No Other, Two Sides was deleted and virtually impossible to find for the longest time. Every time it popped up on Ebay, the reserve bid was like $150 for a worn-out and scratchy vinyl copy. I'd actually never heard it until a re-released edition came out about two years ago. Hear the Wind is the best song on the record, a yearning ballad that's guaranteed to break your little heart. It's a rare moment of excellence amidst a sea of mostly unfocussed, half-baked material, likely a reflection of Clark's inner torment and torturously slow descent into the abyss. The footage I pulled for the song looks like it might be from the 80s or even the early 90s, right before Clark's passing. It's kind of hard to watch because he looks so lost, everything from the goofy ponytail-earning-bolo tie getup, to the hauntingly blank look on his face, to the cheesy Star Search-like set he's been relegated to playing on. Be warned that to watch this footage is to witness a man nearing the end. But there's also a certain dignity in the way he delivers the song. No matter what life did to him, or what he did to himself, Clark always had that beautiful voice, distinctly understated yet perfect for this type of material...

Friday, October 12, 2012

byrdsongs, lxviii

A friend and reader asked me why I’ve been bothering to write about so much mediocre music lately. It’s a fair question, especially since I have other exciting projects in mind for the future. Why not make the future now? I could have ended this series with The Notorious Byrd Brothers, in which case the whole thing would’ve had a happy ending, at least musically speaking. But I didn’t wanna short change the Clarence White era because I have so much admiration for his guitar playing, even though the Byrds studio material over his tenure with the band as an official member is patchy and mixed. And then I wanted to reassess all the post-Byrds bands and solo material in hopes of finding gems I‘d never paid attention to before. So far, the only gems I’ve found are ones I already knew about. I hope that I’ve at least been able to introduce them to folks who’ve never heard them before. …Most of the stuff from the mid 70s is quite frankly forgettable. I’m fond of saying that time redeems all bad music. This may be true of music that’s initially not taken seriously or that’s perceived as a joke, like the Monkees or Herman’s Hermits or the Archies. But time tends not to redeem stuff that’s just tepid and bland, that just is with no real reason for being other than that it may serve as a vehicle through which a record company can extract more value from its roster of talent. No amount of time, in other words, will redeem the second Manassas album or anything by Souther Hillman Furay. Even still, I’m pressing on in order to be thorough. That's just the anal-retentive way I roll. I think I should see this project through to a conclusion that provides some satisfying closure. It’d be a bummer to end things on a bad note. In spite of all this less-than-stellar music we’ve been exposed to over the past few weeks, it’s still the case that the Byrds – McGuinn, Crosby, Hillman, Clark, and even Clarke – are and will always be heroes to me because of what they were able to do over a few heady years in the mid 60s. I'd like to conclude this series in a way that’s worthy of their most enduring legacy. I imagine that this is how Roger McGuinn felt in the mid 70s. He kept making unremarkable records, each time knowing that the music had to be framed inside an FM radio shell, each time trying to make the corporate rock idiom work for him. It wasn't a natural fit, perhaps because he’s way too good of a musician to be having to bend his talent to some prefabricated commercial mold. I hear the stuff and I think, what a waste of great talent. And it’s not his fault. The changing economics of the music industry forced him into a narrowly circumscribed box, leading to material that sounds stunted and lifeless. Cardiff Rose, released in 1976, lends further credence to this diagnosis. What's werid is that the record is produced by Mick Ronson. Rono! On the one hand, with two of my all-time GUITAR GODZ working on the same project, I'd expect the outcome to be so much better than what we end up with here. But on the other hand, let's face it, Rono and McGuinn is a strange mix, the king of trashy power chords and the deft 12-string player with his endlessly intricate passing chords and arpeggios. It's a mismatch, and perhaps this is what accounts for the music's lack of personality. The record has some nice touches here and there, but it’s pretty boring stuff, a collection of songs that all more or less sound similar to one another. There’s nothing distasteful on the record, it’s just dull as hell. One thing that’s different this time around is that the song structures are slightly more folky sounding, indicating that McGuinn's attempts at making convincing corporate country rock have been abandoned in favor of corporate folk rock - CFR - with heavy emphasis on the C and the R. A cover of Joni Mitchell's Dreamland is the one song on Cardiff Rose that has anything vaguely approaching a hook, like a water mirage in the midst of the hottest and driest of hot and dry deserts…

A friend and reader asked me why I’ve been bothering to write about so much mediocre music lately. It’s a fair question, especially since I have other exciting projects in mind for the future. Why not make the future now? I could have ended this series with The Notorious Byrd Brothers, in which case the whole thing would’ve had a happy ending, at least musically speaking. But I didn’t wanna short change the Clarence White era because I have so much admiration for his guitar playing, even though the Byrds studio material over his tenure with the band as an official member is patchy and mixed. And then I wanted to reassess all the post-Byrds bands and solo material in hopes of finding gems I‘d never paid attention to before. So far, the only gems I’ve found are ones I already knew about. I hope that I’ve at least been able to introduce them to folks who’ve never heard them before. …Most of the stuff from the mid 70s is quite frankly forgettable. I’m fond of saying that time redeems all bad music. This may be true of music that’s initially not taken seriously or that’s perceived as a joke, like the Monkees or Herman’s Hermits or the Archies. But time tends not to redeem stuff that’s just tepid and bland, that just is with no real reason for being other than that it may serve as a vehicle through which a record company can extract more value from its roster of talent. No amount of time, in other words, will redeem the second Manassas album or anything by Souther Hillman Furay. Even still, I’m pressing on in order to be thorough. That's just the anal-retentive way I roll. I think I should see this project through to a conclusion that provides some satisfying closure. It’d be a bummer to end things on a bad note. In spite of all this less-than-stellar music we’ve been exposed to over the past few weeks, it’s still the case that the Byrds – McGuinn, Crosby, Hillman, Clark, and even Clarke – are and will always be heroes to me because of what they were able to do over a few heady years in the mid 60s. I'd like to conclude this series in a way that’s worthy of their most enduring legacy. I imagine that this is how Roger McGuinn felt in the mid 70s. He kept making unremarkable records, each time knowing that the music had to be framed inside an FM radio shell, each time trying to make the corporate rock idiom work for him. It wasn't a natural fit, perhaps because he’s way too good of a musician to be having to bend his talent to some prefabricated commercial mold. I hear the stuff and I think, what a waste of great talent. And it’s not his fault. The changing economics of the music industry forced him into a narrowly circumscribed box, leading to material that sounds stunted and lifeless. Cardiff Rose, released in 1976, lends further credence to this diagnosis. What's werid is that the record is produced by Mick Ronson. Rono! On the one hand, with two of my all-time GUITAR GODZ working on the same project, I'd expect the outcome to be so much better than what we end up with here. But on the other hand, let's face it, Rono and McGuinn is a strange mix, the king of trashy power chords and the deft 12-string player with his endlessly intricate passing chords and arpeggios. It's a mismatch, and perhaps this is what accounts for the music's lack of personality. The record has some nice touches here and there, but it’s pretty boring stuff, a collection of songs that all more or less sound similar to one another. There’s nothing distasteful on the record, it’s just dull as hell. One thing that’s different this time around is that the song structures are slightly more folky sounding, indicating that McGuinn's attempts at making convincing corporate country rock have been abandoned in favor of corporate folk rock - CFR - with heavy emphasis on the C and the R. A cover of Joni Mitchell's Dreamland is the one song on Cardiff Rose that has anything vaguely approaching a hook, like a water mirage in the midst of the hottest and driest of hot and dry deserts…Thursday, October 11, 2012

byrdsongs. lxvii

There’s always gonna be topics one wishes to avoid. When my heroes do embarrassing things, I’d rather not talk about it, rather not dwell on it. It’s like with Willie Mays. Nobody wants to think about him being all gimpy in the 1973 World Series, a shell of his former greatness. And I don’t wanna think about Moe Tucker becoming a member of the Tea Party, or Gene Simmons being an all-around douchebag. Roman Polanski raped a 13-yr-old girl. She might've even been 12. That’s horrible, and it’s none of my business, so I’m just gonna watch Knife in the Water, Rosemary’s Baby, and Chinatown, marveling at them all with my blinkers on. I remember how disappointed I was when I learned that Roger McGuinn is Born Again. But does it make me admire him less? Not unless I think about it. Everybody’s got their flaws, even you out there, dear reader, those things you hope won’t be revealed and pray people won’t hold against you when they are. So try being sympathetic and accepting. Does it sound like I’m vamping? I am. Why else would I waste time spouting hollow platitudes about flaws and acceptance and sympathy? Because, really, who am I kidding? I’m the least accepting guy I know when it comes to people’s flaws. I hone in on them so I don’t have to think about my own, which are considerable, believe me. It’s small comfort, though comfort nevertheless, to dwell on the negative, particularly if it’s negativity directed at someone else. That’s a little sick, isn’t it? The way negativity can be comforting. I have a friend from childhood – we’ve become somewhat estranged from one another over the past 20 years or so – but one of the things I loved about him when we were kids was that he was so negative and bitter, a real dark guy, but in a funny way. He wasn’t a sad sack. Well, maybe a little bit of a sad sack but not too much. I’d call him mirthfully negative in a way that was very New York, very Jewish, and very much of apiece with the social pressure cooker that was my Manhattan judeo-bourgeois environment. But something happened at some point in his early adult life. I’m not completely sure what it was. I know he had a fairly serious health scare when he was in college and was hospitalized for awhile. There was even talk he might not make it, but he did, thankfully. In the course of this crisis, however, I think he had some kind of moment of clarity, though this ‘clarity’ paradoxically muddled his thinking and his personality beyond recognition. He began to embrace some kind of very loosely defined spirituality. In my mind, when this happens with a person it’s usually a negative reaction to the realization that life is essentially meaningless. But I won’t get too deeply into that right now. …So he embraces this weird occult stuff, an incomprehensible hodge podge of Aliester Crowley, yoga, Dianetics, and Chinese fortune cookies. And as this awakening (or whatever it was) unfolded, he moved to Frisco and all the things I loved about the guy began to evaporate. He traded in the mirthful negativity for arch optimism and benevolence. I say benevolence but the truth is that it’s a sham, a mask he wears, perhaps even when he’s alone and looking at himself the mirror. The reality is that he’s become a deeply self-centered, self-important, selfish person, a shell of his former greatness, just like Mays in the ’73 series, no less hobbled, just in a different way. He doesn’t wanna criticize anything. He thinks my negativity is narrow-minded. There’s no point any longer in telling him that it’s better to be critical and discerning than to be accepting of every pile of bullshit that gets thrown in your direction. I keep telling myself that this isn’t really who he is, that he’ll come back around to being the guy I held in such high esteem, once upon a time. But deep down I know that, while he’s smart enough to know who he really is, he’ll never let that guy come out again. He’s too deeply invested now in this new thing he wants to be. He has been for a long time. He’s too far gone, too old, too lazy, too permanently damaged. And why am I telling you all this? It should be obvious by now. I’ll do almost anything not to have to talk about Souther Hillman Furay…

There’s always gonna be topics one wishes to avoid. When my heroes do embarrassing things, I’d rather not talk about it, rather not dwell on it. It’s like with Willie Mays. Nobody wants to think about him being all gimpy in the 1973 World Series, a shell of his former greatness. And I don’t wanna think about Moe Tucker becoming a member of the Tea Party, or Gene Simmons being an all-around douchebag. Roman Polanski raped a 13-yr-old girl. She might've even been 12. That’s horrible, and it’s none of my business, so I’m just gonna watch Knife in the Water, Rosemary’s Baby, and Chinatown, marveling at them all with my blinkers on. I remember how disappointed I was when I learned that Roger McGuinn is Born Again. But does it make me admire him less? Not unless I think about it. Everybody’s got their flaws, even you out there, dear reader, those things you hope won’t be revealed and pray people won’t hold against you when they are. So try being sympathetic and accepting. Does it sound like I’m vamping? I am. Why else would I waste time spouting hollow platitudes about flaws and acceptance and sympathy? Because, really, who am I kidding? I’m the least accepting guy I know when it comes to people’s flaws. I hone in on them so I don’t have to think about my own, which are considerable, believe me. It’s small comfort, though comfort nevertheless, to dwell on the negative, particularly if it’s negativity directed at someone else. That’s a little sick, isn’t it? The way negativity can be comforting. I have a friend from childhood – we’ve become somewhat estranged from one another over the past 20 years or so – but one of the things I loved about him when we were kids was that he was so negative and bitter, a real dark guy, but in a funny way. He wasn’t a sad sack. Well, maybe a little bit of a sad sack but not too much. I’d call him mirthfully negative in a way that was very New York, very Jewish, and very much of apiece with the social pressure cooker that was my Manhattan judeo-bourgeois environment. But something happened at some point in his early adult life. I’m not completely sure what it was. I know he had a fairly serious health scare when he was in college and was hospitalized for awhile. There was even talk he might not make it, but he did, thankfully. In the course of this crisis, however, I think he had some kind of moment of clarity, though this ‘clarity’ paradoxically muddled his thinking and his personality beyond recognition. He began to embrace some kind of very loosely defined spirituality. In my mind, when this happens with a person it’s usually a negative reaction to the realization that life is essentially meaningless. But I won’t get too deeply into that right now. …So he embraces this weird occult stuff, an incomprehensible hodge podge of Aliester Crowley, yoga, Dianetics, and Chinese fortune cookies. And as this awakening (or whatever it was) unfolded, he moved to Frisco and all the things I loved about the guy began to evaporate. He traded in the mirthful negativity for arch optimism and benevolence. I say benevolence but the truth is that it’s a sham, a mask he wears, perhaps even when he’s alone and looking at himself the mirror. The reality is that he’s become a deeply self-centered, self-important, selfish person, a shell of his former greatness, just like Mays in the ’73 series, no less hobbled, just in a different way. He doesn’t wanna criticize anything. He thinks my negativity is narrow-minded. There’s no point any longer in telling him that it’s better to be critical and discerning than to be accepting of every pile of bullshit that gets thrown in your direction. I keep telling myself that this isn’t really who he is, that he’ll come back around to being the guy I held in such high esteem, once upon a time. But deep down I know that, while he’s smart enough to know who he really is, he’ll never let that guy come out again. He’s too deeply invested now in this new thing he wants to be. He has been for a long time. He’s too far gone, too old, too lazy, too permanently damaged. And why am I telling you all this? It should be obvious by now. I’ll do almost anything not to have to talk about Souther Hillman Furay…Wednesday, October 10, 2012

byrdsongs, lxvi

Hippy Midlife Crisis Music (HMCM), a subgenre of Corporate Hippy Music (CHM), and a branch on the same family tree that gave us Corporate Country Rock (ccr), is a style that, more than anything else, puts me in a mood to hear the low hiss of Dave Mustaine’s disdainful nihilism. Nash and Crosby’s Wind on the Water is perhaps the seminal HMCM record. Personally, if I’m jonesing for inoffensive MOR, I’d rather hear the likes of Seals and Crofts, America, Cat Stevens, Al Stewart, or Gordon Lightfoot, because the thought that Wind on the Water is a record by a former Byrd and a former Hollie upsets me a little bit, makes me wanna look at nasty facial porn. …Remember that nauseating 80s movie about those boomers who have a reunion after one of their college buddies commits suicide? Thinking… Thinking… William Hurt… Glenn Close… A navel gazing apologia for the hippie cum yuppie generation. Lots of Motown music… But no blacks within a ten-mile radius of the script… Jeff Goldblum… God I hate that motherfucker more than the hemorrhoids bulging out my asshole… THE BIG CHILL! That’s it, The Big Chill. Yes, well, Wind on the Water is The Big Chill before The Big Chill, or The Big Chill before the big chill, as it were, in which the hippies are getting older, if not wiser, experiencing the vicissitudes of life itself after having tried to opt out for so long. But the music doesn’t resonate with me because one of the unfortunate legacies of the 60s is that of adults who never grow up, never mature, yet in spite of this they have children of their own, and they indulge these children beyond saving, because the only constant in their lives has been indulgence, so their children grow up to be monsters, and total pussies, pussies who know nothing of restraint, nothing of limits, and won’t take no for an answer, can’t take no for an answer, don’t even know what NO means. This is what makes a record like Wind on the Water so worthy of mockery. Nash and Crosby would have us believe that the hippies have gained perspective and maturity with age. I wonder if this is the same perspective Crosby had when his head was buried in a salad bowl of blow… The music as music is ok. It’s unremarkable mid-70s session playerish sounding stuff, kind of like Jackson Browne without the intelligence, the type of thing that’s best heard as barely noticeable aural wallpaper at LAX, where the laughable lyrical content of the music would be obliterated by the white noise of the masses and their beeping gadgetry. It’s too bad the title Music for Airports is already taken, because that’s essentially what this stuff is…

Tuesday, October 9, 2012

byrdsongs, lxv

Maybe the reason Roger McGuinn kept the Byrds going for about two years too long is that he had an inkling of how diminished he would become as a solo artist. The one word I keep coming up with in reassessing his 70s solo material is resigned. It just doesn’t sound like he’s that into it. I think post-free-form FM radio had a depressing effect on McGuinn, in the broadest sense of the word depressing. Perhaps depressant is more precise. The music has almost no spark. I don’t blame McGuinn for this, at least not entirely. I’m sure that as the music business became more about business than music, the parameters of what McGuinn could do were increasingly limited. His 70s albums are garden variety corporate rock, nice enough but hardly anything you’d care to hear more than once or twice, hardly memorable. This from the man who’d made some of the most memorable music of all time. What’s interesting is that Brian Wilson and Paul McCartney - both of whom are McGuinn’s peers, not only generationally but also in terms of raw musical talent – made the transition more compellingly. The rock music they made in the 70s had a pop heart and a pop accent. Even songs as cloying as this, and as shamelessly nostalgic as this and this, are catchy and demand repeated hearings. McGuinn’s stuff doesn’t have the same impact, probably because the pop heart’s been ripped out, the pop accent unlearned. The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain. With his cover of Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door, off the forgettable Roger McGuinn & Band, he returns to a reliable source of inspiration and almost pulls it off. Almost. The flanged 12-string jangle you hear at the beginning proves to be something of a false dawn. Once the irritating (focus group tested?) second guitar* kicks in, I just wanna get back in bed and dream a dream in which I'm 16 and it's 1965...**

*Another general pop life music rule: Slide guitar/lap steel (or whatever that thing is polluting tonight’s song) can be filed with harmonica, black choir singers, and wind instruments under things that, with rare exceptions, always make (white) pop/rock songs sound worse than they otherwise would be in their absence.

**In this dream I'm also flat footed, or gay, or some such.

**In this dream I'm also flat footed, or gay, or some such.

Sunday, October 7, 2012

byrdsongs, lxiv

I gotta be honest with you: I’ve been dreading the moment when we would arrive at the Souther Hillman Furay Band. The best I can say for this utterly transparent attempt to manufacture a CSN-type supergroup is that they are perhaps not quite as horrible as they are almost unanimously made out to be. But the stuff is completely devoid of any shred of inspiration. There’s no joy in the music at all, which is what inevitably happens when the only motivating factor is the receipts. The paradox is that music made only for money almost never makes money, or at least it never makes the serious money it's intended to extract. The Eagles are the exception that proves this rule… If the SHF Band had simply been Furay and Hillman (the Springfield + the Byrds), they might’ve had a fighting chance to do something worthwhile. I place the blame on two people for the grimness of the music: Firstly, there’s JD Souther, a rock mercenary if ever there was one, and whose name should really be DB Souther; 2) David Geffen, who hatched the idea for this product, likely out of his corner office at Asylum headquarters, where many other equally soulless / manipulative / venal / greedy / tedious / completely market-driven ideas were undoubtedly also birthed. What’s amazing to me is that SHF went on to release a second album, just in case you might’ve been thinking that the first was the absolute bottom of the barrel…

Thursday, October 4, 2012

byrdsongs, lxiii

Lady of the North is autobiographical, allegorical/symbolic, and heartbreaking. The pastoral verses depicting peace, love and contentment are each time answered with others expressing the anguish and dread that, for Clark, always seemed to be just around the corner. I can relate to this. Some of us have a hard time experiencing unadulterated happiness because we know it's fleeting, and the pain of losing it is worse than not having it at all. I’m only half kidding when I tell friends and loved ones that I don’t do ‘in the moment.’ …There’s a weird disconnect on much of No Other between the raw and abject sadness of its emotional tone and the slickness of the production value. Depression isn’t supposed to sound so polished and corporate. This is what I meant yesterday when I said that No Other is a strange album. The songs are good but the record as a whole is…I don’t know…there’s something a bit off about it. It doesn’t cohere somehow. It’s far more worthy of your attention than anything McGuinn, Hillman or Crosby did in the mid to late 70s, but it’s still flawed in a way I can’t completely articulate. Part of it is that it’s a rock album and Gene Clark is a pop guy. He’s at his best when he’s doing three-minute love songs with great hooks, multipart harmonies and tambourines. He’s in his element when the music is light and deft, even if it’s sad ‘n blue. Keep it simple, keep it compact, don’t ramble. Verse-chorus-bridge-chorus-verse-done. The music on No Other is the opposite of this. A few of the songs are over six bloody minutes long! That’s not what we’re looking for with Gene Clark. …I may be overestimating the extent to which it was possible for Clark - coming from where he came from - to have made a pop record in the mid 70s. Even Paul McCartney, Mr. Pop, was making turgid rock records at the time. Band on the Run is a fun album, very catchy, but it’s definitely hard and even heavy. …The movement from mid 60s pop to mid 70s rock only seems like devolution now, with several decades hindsight. At the time it sounded and felt like progression and growth. I can remember a time, as a little kid, when I definitely preferred the White Album to With the Beatles. So it may not be entirely fair for me to complain that No Other is all rock, no pop. Even still, the sadness I feel when I hear it is not only a reaction to the music’s content but also to its awkwardly navigated form. The record's downbeat strangeness comes from Clark's poignant effort to find his way amidst world that's passed him by...

Wednesday, October 3, 2012

byrdsongs, lxii

Gene Clark’s No Other is easily the most compelling mid-70s record by a former Byrd. But this doesn’t make hearing it a fun time. It’s a pretty strange and quite frankly disturbing collection of songs, one that, to me, seems to mark the start of a long drift into oblivion for Clark. The album is slick and glossy sounding in the manner of corporate country rock, but it’s too somber to catch fire with a mass audience, and too weird to be marketed effectively. There’s nothing at all poppy about No Other. It was deleted for a long time and I can remember when it was an almost impossible record to find. I stumbled across a pristine copy purely by accident at a yard sale on Fountain Avenue in West Hollywood. I couldn’t believe the Russian guy only wanted a quarter for it… The album opens with Life’s Greatest Fool, a song that puts Clark’s signature happy/sad songwriting approach to work in a country two-step context. Over the otherwise sunny key of G major, he tells us that‘too much loneliness makes you grow old.’ Wow. That’s painful to hear, if also quite true. Elsewhere he sings, ‘we all need a fix, at a time like this, but doesn’t it feel good to stay alive?’ Whether or not this is a reference to the alcoholism he struggled with, it sounds like a desperate plea for help and understanding. This is what makes No Other so difficult for me to hear, even though much of the music is very good. I feel like I’m listening to someone who’s drinking himself to death, which is such a horrible way to go out. It’s amazing to me that he lived for another 17 years and even managed to have bursts of creative productivity in that time. So much of Gene Clark’s music up to No Other is joyful even when it’s so very sad. This is what you sign up for if you’re a pop lifer. It’s not masochism, necessarily, but rather the capacity to transform life’s disappointments through the power of music. No Other doesn’t fall into this category. If you listen to the record carefully, the music will bring you down. This doesn’t mean you should avoid it, but just know that the pop life catharsis – and Gene Clark gave us so many of these – won’t be forthcoming. It’s like, ‘ok, this is what profound sadness feels like.’ Sometimes I can go there and appreciate No Other’s deep intensity, but a lot of the time it’s just too much pain and sorrow for me to handle…